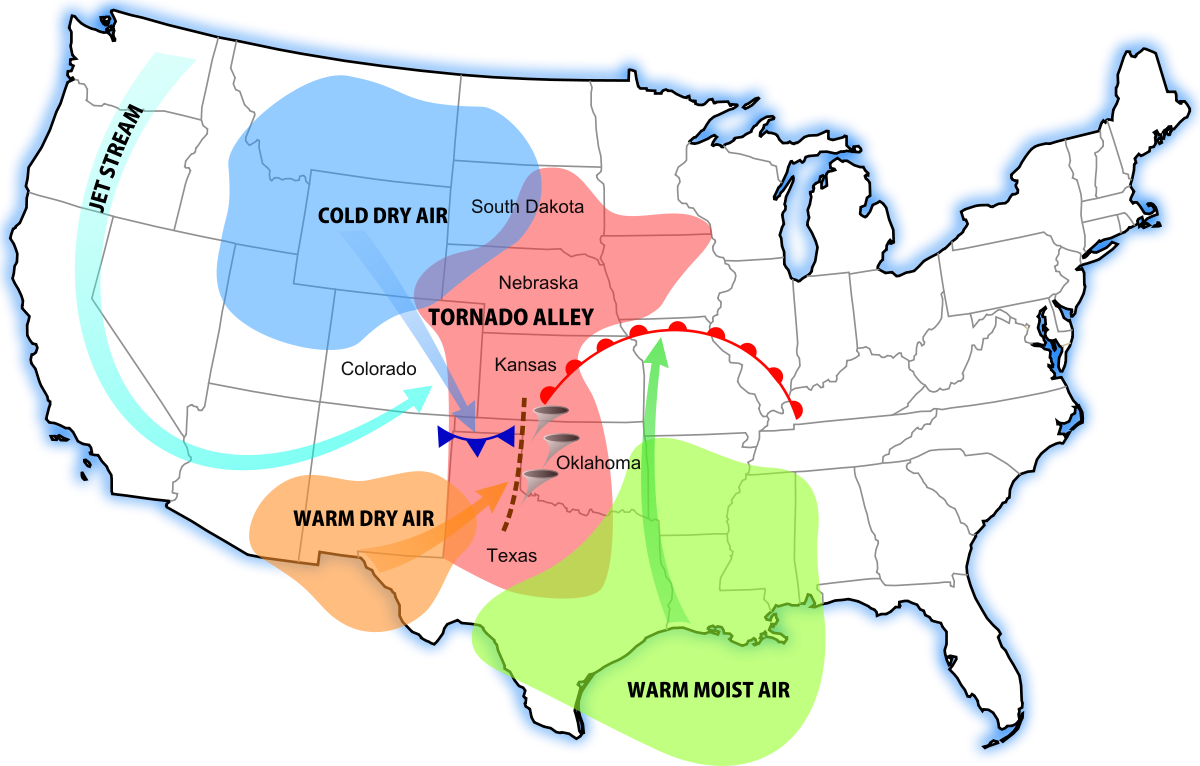

Tornado Alley is a loosely defined location of the central United States and Canada where tornadoes are most frequent. The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project to study severe weather in areas of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska. Tornado climatologists distinguish peaks in activity in certain areas and storm chasers have long recognized the Great Plains tornado belt.

As a colloquial term there are no definitively set boundaries of Tornado Alley, but the area common to most definitions extends from Texas, through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Arkansas, North Dakota, Montana, Ohio, and eastern portions of Colorado and Wyoming. Research suggests that the main alley may be shifting eastward away from the Great Plains, and that tornadoes are also becoming more frequent in the northern and eastern parts of Tornado Alley where it reaches the Canadian Prairies, Ohio, Michigan, and Southern Ontario.

Anyone who’s ever seen the movie “Twister” is aware of Tornado Alley — known for its reliable and, at times, hyperactive swarms of tornadoes that swirl across the landscape like clockwork each spring. The term brings to mind the strip of land stretching across Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas. But meteorologists fear that imaginary zone may be leaving out areas at an even greater risk for damaging tornadoes.

Tornado season may ramp up again in late May

In recent years, the South has come to prominence for its encounters with violent tornadoes. As recently as Easter weekend, an outbreak of more than 150 tornadoes wrought havoc across Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee and even into the Carolinas. A week later, a high-end EF4 tornado struck near the previous hardest-hit counties in Mississippi, marking the third EF4 to hit within a 15-mile radius over the course of seven days.

Last month was the second-most active April for tornadoes

Meteorologists argue this corridor of enhanced tornado activity across the South isn’t just another tornado hot spot — it’s a bona fide extension of Tornado Alley. In fact, many atmospheric scientists say the term “Tornado Alley” is a misnomer and fails to convey where the greatest tornado risks may lie. Some contend portions of the South are among the most vulnerable to tornadoes in the world.

A troubled history with tornadoes

Preliminary tornado reports through the end of April in 2020. (NOAA/SPC)

April 27, 2011, was a day that will live in meteorological infamy. A morning squall line of vicious thunderstorms plowed across Mississippi and Alabama, unleashing a band of quick-hitting tornadoes and winds that knocked out power to a million homes. An EF3 tornado hit Cordova, Ala. — a town that would be struck hours later by an even more violent tornado. Tornadoes are rated on the 0-to-5 Enhanced Fujita scale.

The atmosphere reloaded that afternoon, giving rise to what’s often regarded as the most prolific tornado outbreak in recorded history. Repeated rounds of violent tornadoes, including four EF5s, resulted in hundreds across Mississippi and Alabama as seemingly endless rotating supercell thunderstorms marched across the state. Some storms traveled hundreds of miles. All told, more than 350 tornadoes accompanied the days-long outbreak.

Already in 2020, tornadoes have struck Nashville; Birmingham, Ala.; Atlanta; Chattanooga, Tenn.; and Charlotte — making this year to date the deadliest for tornadoes since 2011. Mississippi recorded its widest tornado on record.

2.25 mile wide Mississippi tornado was nation's third largest on record

Most of the deaths from tornadoes have occurred outside the traditionally regarded Tornado Alley but well within the zone of where vicious tornadoes are common. Some experts agree it’s time to abandon the term.

Where do tornadoes occur?

Storm chasers flock to a tornado near Bennington, Kan., in May 2013. (Ian Livingston/The Washington Post)

“To be honest, I hate the term ‘Tornado Alley,'” said Steven Strader, an atmospheric scientist at Villanova University specializing in severe weather risk mitigation. He says he hates even more the term “Dixie Alley,” used to describe the busy swath of tornado activity in the South.

“What people need to understand is that if you live east of the continental divide, tornadoes can affect you,” said Strader.

The geographical distribution of tornadoes across the Lower 48 has been the subject of investigation for years. One study conducted by P. Grady Dixon, a physical geographer at Fort Hays State University in Kansas, found that the Deep South is in essence a continuation of the more traditionally recognized Tornado Alley.

A tornado in eastern New Mexico on May 26. (Cameron Nixon/Twitter)

“I’m of the opinion that Tornado Alley is an outdated, misleading concept in general,” said Grady in an interview with The Post. “But I’m realistic in that I know [the term] is not going away anytime soon.”

His project found, on a basis of tornado density and path length, the most tornado-prone location in the country isn’t in Oklahoma or Kansas — it’s Smith County, Miss. Though Grady’s paper was published in 2010, anecdotal evidence since suggests his finding is spot on: That region of Mississippi has been close to ground zero for the country’s worst twisters so far this year.

In April 2011, a tornado moves through Tuscaloosa, Ala. (Dusty Compton/Tuscaloosa News/AP)

On the whole, Grady’s work revealed not only that Mississippi and Louisiana average the most “tornado days” per year, but that an enormous circular swath from the Midwest and Corn Belt down through the Plains and South are one large breeding ground for tornadoes.

Save for a small downtick in tornado counts over the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks, there’s virtually nothing separating — or distinguishing — traditional Tornado Alley from the South.

“The term ‘alley’ is restrictive, suggests something that is spatially long and narrow so to speak,” explained Grady. “We have a tornado region that’s essentially the eastern 40 percent of the continental U.S.”

A tornado supercell in Nebraska on May 26, 2013. (Ian Livingston/The Washington Post)

“Even just that paper, we’ve learned tons of things,” Grady continued. “I don’t think a gap [between the Plains and the South] exists. … Maybe there’s a low spot in activity in Missouri, but if you’re drawing a line from central Mississippi to south central Kansas, there’s no gap. Central Illinois to eastern Nebraska, there’s no gap. They’re connected.”

Deep South tornado dangers

To make matters worse, Grady uncovered evidence suggesting tornadoes in the South, or Dixie Alley, travel farther thanks to their faster speeds. Those longer paths make tornadoes more likely to cause damage in the South, especially before the mid-spring and summer months and again later in the fall.

“Storms tend to move faster during the cool season,” Grady said. “I think they are actually longer [tornado] paths throughout the Deep South. Look at the speeds of some of these storms from that Easter event. … We were having some storms move at 70 mph.”

Two strong tornadoes may have merged over South Carolina during Easter outbreak

Tornado are also as common — or even more frequent — in the South as they are on the Plains. “That region gets probably the greatest number of tornadoes, the Southeast,” Strader said.

So why has Tornado Alley’s colloquial definition never really included the South? It boils down to public perception, rooted in years of storm chasing, cinematography and geography.