질량 보존 법칙(質量保存法則, law of conservation of mass)

닫힌 계의 질량이 화학 반응에 의한 상태 변화에 상관없이 변하지 않고 계속 같은 값을 유지한다는 법칙이다. 물질은 갑자기 생기거나, 없어지지 않고 그 형태만 변하여 존재한다는 뜻을 담고 있다. 다시 말해, 닫힌계에서의 화학 반응에서, '(반응물의 질량) = (결과물의 질량)'이라는 수식을 만족한다. 질량 보존 법칙은 비상대론적인 법칙이며, 상대성이론을 고려할 경우 상황은 조금 복잡해진다. 상대론을 고려할 경우에도 에너지 보존의 법칙은 성립한다.

이 법칙은 근대 화학의 아버지 앙투안 라부아지에가 최초로 정식화하였다. 그러나 이전에도 미하일 로모노소프(Mikhail Lomonosov) 등이 언급한 바가 있다.

하지만 아인슈타인의 특수상대성이론에 의하면 질량이 에너지로도 변환될 수 있다.

질량/물질 보존의 예외

물질은 완벽하게 보존되지 않는다.

물질 보존의 법칙은 특수 상대성 이론이나 양자역학을 고려하지 않은 고전적 이론에서만 참인 근사적인 물리 법칙으로 생각될 수 있다. 그것은 특정 높은 에너지 활용을 제외하고는 거의 참이다. 보존의 개념에 특정한 어려움은, ‘물질’이 과학적으로 잘 정의된 단어가 아니라는 점이다. 그리고 물질들이 ‘물질’이라고 생각될 때, (예를 들어 전자나 양전자) 등은 광자를 생성하기 위해 없어진다. (광자는 종종 물질로 생각되지 않는다) 그러면 물질의 보존은 고립계에서도 참이 되지 않는다. 그러나, 물질 보존은 방사능과 핵반응이 포함되지 않는 화학 반응에서 안전하게 추정될 수 있다. 물질이 보존되지 않더라도, 계 안에서의 질량과 에너지의 총 합은 보존된다.

열린계와 열역학적으로 닫힌 계

또한 질량은 열린계에서 일반적으로 보존되지 않는다. 계 내부나 외부로 다양한 형태의 에너지들이 투입될 수 있거나 나갈 수 있는 경우가 그런 예다. 그러나, 다시 말하지만 방사능과 핵반응이 포함되지 않는다면, 계에서 도망가는 열, 일, 전자기적 방사선은 계의 질량의 감소로 측정하기에는 사실 너무 작다. 고립계에서의 질량 보존 법칙 (질량과 에너지가 전부 닫힌계) 은 어떤 관성계에서 봐도 계속 현대 물리학에서 참으로 여겨진다. 이것의 이유는, 상대성 방정식이 심지어 ‘질량이 없는’ 입자들, 예를 들어 광자들이 고립계에 질량과 에너지를 더한다고 보이기 때문이다. 질량 (물질이 아니지만)이 에너지가 도망가지 않는 계의 과정에서 엄격하게 보존되도록 허락한다. 상대성 이론에서는, 다른 관찰자들이 주어진 계에서의 보존된 특정 값에 동의하지 않을 수 있다. 그러나 각각의 관찰자들은 이 값이 시간에 따라 변하지 않는다는 것에 동의할 것이다. (계가 모든 것에 대해 고립되어 있다면)

일반 상대성 이론

일반 상대성 이론에서는, 팽창하는 부피의 우주에서 광자의 변치 않는 총 질량은 적색 이동 때문에 감소할 것이라고 한다. 그래서 질량과 에너지의 보존은 이론에서 에너지로 만들어진 다양한 수정들에 의존한다. 그러한 계들의 변하는 중력 퍼텐셜 에너지 때문이다.

알베르트 아인슈타인

질량-에너지 등가법칙

The Law of Conservation of Mass

The Law of Conservation of Mass dates from Antoine Lavoisier's 1789 discovery that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions. In other words, the mass of any one element at the beginning of a reaction will equal the mass of that element at the end of the reaction. If we account for all reactants and products in a chemical reaction, the total mass will be the same at any point in time in any closed system. Lavoisier's finding laid the foundation for modern chemistry and revolutionized science.

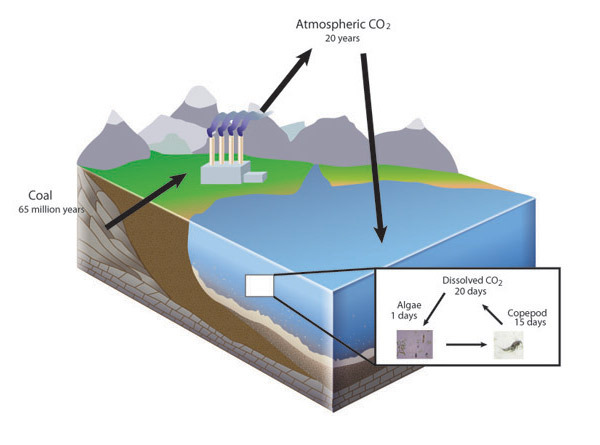

The Law of Conservation of Mass holds true because naturally occurring elements are very stable at the conditions found on the surface of the Earth. Most elements come from fusion reactions found only in stars or supernovae. Therefore, in the everyday world of Earth, from the peak of the highest mountain to the depths of the deepest ocean, atoms are not converted to other elements during chemical reactions. Because of this, individual atoms that make up living and nonliving matter are very old and each atom has a history. An individual atom of a biologically important element, such as carbon, may have spent 65 million years buried as coal before being burned in a power plant, followed by two decades in Earth's atmosphere before being dissolved in the ocean, and then taken up by an algal cell that was consumed by a copepod before being respired and again entering Earth's atmosphere (Figure 1). The atom itself is neither created nor destroyed but cycles among chemical compounds. Ecologists can apply the law of conservation of mass to the analysis of elemental cycles by conducting a mass balance. These analyses are as important to the progress of ecology as Lavoisier's findings were to chemistry.

Life and the Law of Conservation of Mass

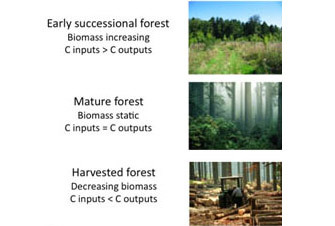

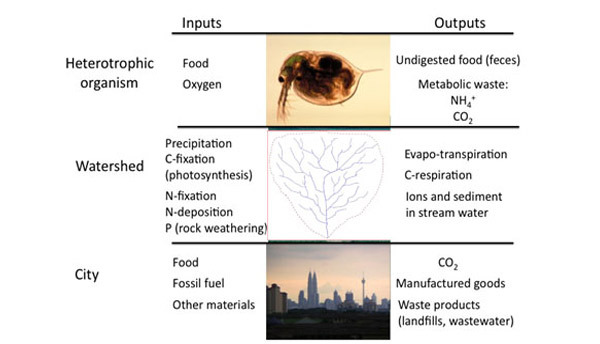

Ecosystems can be thought of as a battleground for these elements, in which species that are more efficient competitors can often exclude inferior competitors. Though most ecosystems contain so many individual reactions, it would be impossible to identify them all, each of these reactions must obey the Law of Conservation of Mass — the entire ecosystem must also follow this same constraint. Though no real ecosystem is a truly closed system, we use the same conservation law by accounting for all inputs and all outputs. Scientists conceptualize ecosystems as a set of compartments (Figure 2) that are connected by flows of material and energy. Any compartment could represent a biotic or abiotic component: a fish, a school of fish, a forest, or a pool of carbon. Because of mass balance, over time the amount of any element in any one of these compartments could hold steady (if inputs = outputs), increase (if inputs > outputs), or decrease (if inputs < outputs). For example, early successional forests gain biomass as trees grow and thus act as a carbon sink (Figure 3). In mature forests, the amount of carbon taken up through photosynthesis may equal the amount of carbon respired by the forest ecosystem, so there is no net change in stored carbon over time. When a forest is cut (and especially if trees are burned to clear land for agriculture), this stored carbon reenters the atmosphere as CO2. Mass balance ensures that the carbon formerly locked up in biomass must go somewhere; it must reenter some other compartment of some ecosystem. Mass balance properties can be applied over many scales of organization, including the individual organism, the watershed, or even a whole city (Figure 4).

Mass Balance of Elements in Organisms

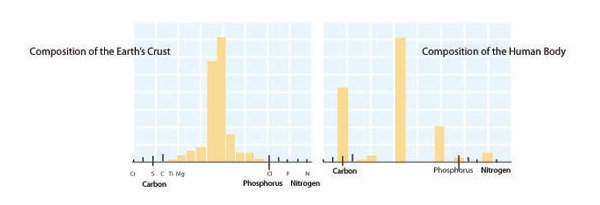

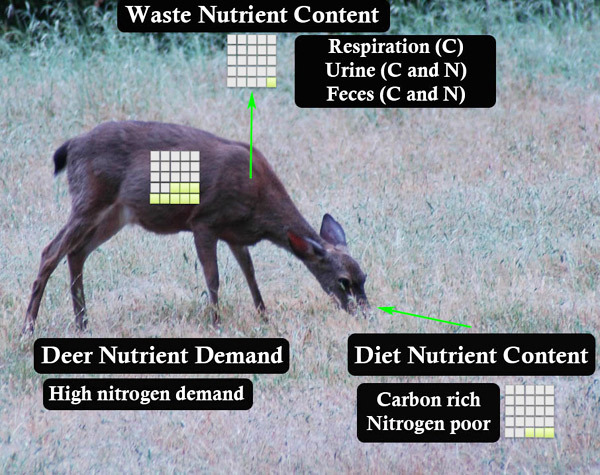

Each organism has a unique, relatively fixed, elemental formula, or composition determined by its form and function. For instance, large size or defensive structures create particular elemental demands. Other biological factors such as rapid growth can also influence elemental composition. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is the biomolecular template used in protein synthesis. RNA has a high phosphorus content (~9% by mass), and in microbes and invertebrates RNA accounts for a large fraction of an organism's total phosphorus content. As a result, fast-growing organisms such as bacteria (which can double more than 6 times per day) have especially high phosphorus content and therefore demands. By contrast, among vertebrates structural materials such as bones (made of calcium phosphate) account for the majority of an organism's phosphorus content. Among mammals, black-tailed deer (Odocoileus columbianus; Figure 6) have a relatively high phosphorus demand due to their annual investment in calcium- and phosphorus-rich antlers. Failure to meet elemental demands can lead to poor health, limited reproduction, and even extinction. The extinction of the majestic Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) is thought to have been caused by the shortened growing season that occurred during the last ice age, which reduced the availability of the calcium and phosphorus these animals needed to grow their enormous antlers.

Obtaining the resources required for metabolism, growth, and reproduction is one of the central challenges of life. Animals, particularly those that feed on plants (herbivores) or detritus (detritivores), often consume diets that do not include enough of the nutrients they need. The struggle to obtain nutrients from poor quality diets influences feeding behavior and digestive physiology and has led to epic migrations and seemingly bizarre behavior such as geophagy (feeding on materials such as clay and chalk). For example, the seasonal mass migration of Mormon crickets (Anabrus simplex) across western North America in search of two nutrients: protein and salt. Researchers have shown that the crickets stop walking once their demand for protein is met (Figure 7).

The flip side of the struggle to obtain scarce resources is the need to get rid of excess substances. Herbivores often consume a diet rich in carbon — think potato chips, few nutrients but lots of energy. Some of this material can be stored internally, but this is a limited option and excess carbon storage can be harmful, just as obesity is harmful to humans. Thus, animals have several mechanisms for getting rid of excess elements. Excess nutrients are released in feces or urine or sometimes it is respired (i.e., released as carbon dioxide). This release of excess nutrients can influence both food webs and nutrient cycles.

Mass Balance in Watersheds

Ecologists have often used naturally delineated ecosystems, such as lakes or watersheds, for applying mass balances. A forested watershed receives inputs of carbon through photosynthesis, inputs of nitrogen from nitrogen-fixing bacteria, as well as through the deposition of atmospheric nitrogen, inputs of phosphorus from the slow weathering of bedrock, and inputs of water from precipitation. Outputs include gaseous pathways (e.g., H2O losses through evapotranspiration, CO2 production as respiration, N2 produced by denitrifying bacteria) and dissolved pathways (nutrients and carbon dissolved in stream water). Outputs also include material transport across ecosystem boundaries, such as the movement of migratory animals or harvesting trees in a forest.

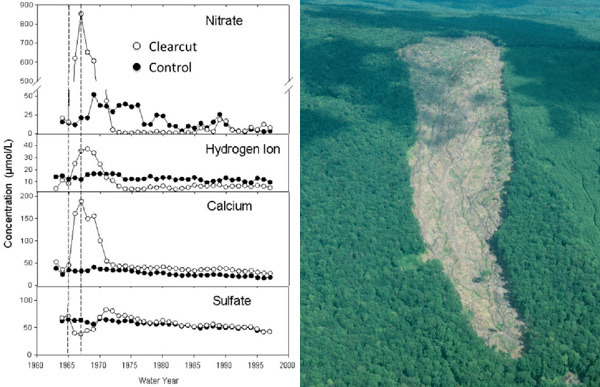

The Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, USA, has been the site of ecosystem mass balance studies since the 1960s. This landscape has similar-sized, discreet watersheds drained by streams and underlain by impermeable bedrock. By installing V-notch weirs, investigators could precisely and continuously measure stream discharge. By measuring the concentration of nutrients and ions in stream water, they could quantify the losses of these materials from the ecosystem. After calculating inputs to the ecosystem (by sampling precipitation, dry deposition, and nitrogen fixation), they could also construct mass balances. Additionally, researchers could experimentally manipulate these watersheds to measure the effects of disturbance on nutrient retention. In 1965, an entire experimental watershed was whole-tree harvested, resulting in large increases in nitrate and calcium losses relative to an uncut reference watershed (Figure 8). By studying inputs and outputs, an understanding of the internal functioning of the ecosystem within the watershed was obtained.

Mass Balance in Human-Dominated Ecosystems

Mass balance constraints apply everywhere, even to highly altered ecosystems such as cities or agricultural fields. Cities import food, fuel, water, and other materials and export materials such as manufactured goods. Cities also produce large quantities of waste products — with solid waste sent to landfills, CO2 (and other pollutants) produced from the combustion of fossil fuels being released to the atmosphere. Nutrients from sewage and from fertilizer runoff can end up in rivers where they will fertilize downstream aquatic ecosystems.

Human agricultural systems can also be analyzed using a mass-balance, ecosystem approach. Traditional agricultural practices emphasized efficiency, with most production staying on the farm — food for livestock was produced on the farm, food for farmers' families was produced on the farm, and plant and animal waste was composted for use as fertilizer on the farm. As a result, the amount of material cycling within the farm "ecosystem" was large relative to the inputs and outputs to the system (a relatively closed ecosystem). By contrast, modern industrial agriculture emphasizes maximizing yields over efficiency. Farmers import fertilizer in large amounts (often far exceeding the amounts that crops can use) and grow and export commodity crops. Ironically, in these highly open ecosystems (where inputs and outputs can far exceed internal cycling), food for farmers' families must often be imported as well. Highly productive agricultural systems are critical in feeding the world's growing human population, but as many of the ingredients of modern agriculture (e.g., water, petroleum, phosphorus) become increasingly limiting over the next century (due to depleted geologic deposits), we will be faced with the challenge of increasing the efficiency of these systems. Just as the constraints of mass balance provide a useful tool for ecologists in studying natural ecosystems, mass balance also ensures that the increase in human population and material consumption that has characterized the past 200 years cannot continue indefinitely.