마르틴 부버, 나와 너

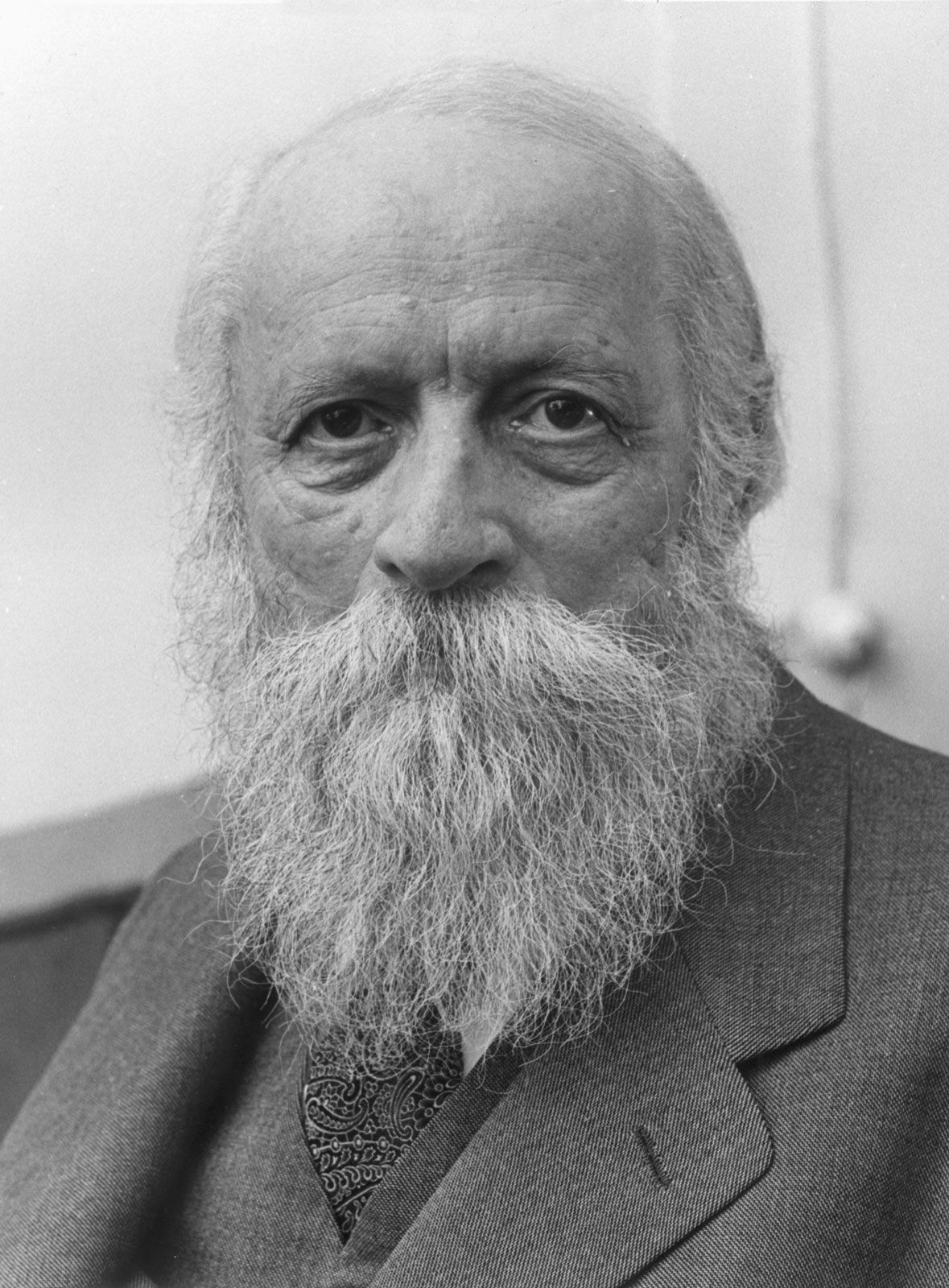

마르틴 부버(Martin Buber, 1878년 2월 8일 ~ 1965년 6월 13일)

오스트리아 빈에서 태어난 유대인 철학자. 당시 동유럽 유대인의 학문적 중심지였던 렘베르크에서 하스칼라(유대교 계몽정신) 운동의 지도자였던 조부 살로몬 부버 밑에서 어린 시절을 보냈다. 1904년 빈 대학에서 '개체화 문제의 역사적 계보'라는 논문으로 철학 박사 학위를 받은 후, 문서 운동과 교육 운동에 힘썼으며, 히브리어 '구약성서'를 현대 독일어로 번역했다. 불후의 명저 '나와 너'를 출간한 1923년에는 프랑크푸르트 대학 교수로 초빙받아 유대교 철학을 비롯하여 윤리학 및 종교사를 강의하게 되는데 1934년 나치에 의해 교수직을 박탈당하게 된다. 1936 년 팔레스티나로 이주해서 1951년까지 예루살렘의 히브리 대학 사회학 교수로 있으면서 새로운 종교적, 문화적 시온주의 운동을 펼쳤다. 1951년 히브리 대학에서 은퇴하고 1949년에 자신이 설립한 예루살렘 성인교육원 원장이 되었다. 미국으로 몇 차례 강연 여행을 했으며. 1965년 예루살렘에서 87세의 나이로 그의 위대한 '대화의 삶' 을 마쳤다. 저서로는 '종교의 철학', '대화', '단독자에 대한 물음', '대화의 삶', '인간의 문제', '신앙의 두 유형', '유토피아로 가는 오솔길', '선과 악의 모습', '하시디즘의 메시지', '대화의 원리' 등이 있다. 작은 분량이지만 6년에 걸쳐 심혈을 길울여 펴낸 '나와 너'는 유럽 대륙에 엄청난 영향을 끼쳤으며 프롬, 베르쟈예프, 만하임, 데일리, 니버 같은 철학자와 교육학자들에게 깊은 영감을 주었다.

세계적인 교양서이자 우리 시대의 살아 있는 고전. 인간 본질에 대한 통찰로 신학뿐만 아니라 문화 전반에 걸쳐 많은 영향을 끼친 마르틴 부버의 대표작이다. 부버는 이 책에서 세상에는 '나와 너'(Ich-Du)의 관계와 '나와 그것'(Ich-Es)의 관계가 존재하는데, 참다운 삶을 살기 위해서는 '나와 너'의 관계를 맺어야 한다고 주장한다. 그는 인간으로서의 가치와 존엄성을 잃어버리는 현대의 비극은 인간과 인간 사이의 참된 관계와 대화가 상실되었기 때문이라고 진단하며 만남과 대화야말로 인간의 삶에 있어서 가장 근원적인 모습이라고 말한다. 참된 관계와 대화가 상실된 오늘의 세상에서 부버의『나와 너』는 우리에게 참된 삶의 가치를 일깨워줄 것이다.

세계적인 교양서이자 우리 시대의 살아 있는 고전. 인간 본질에 대한 통찰로 신학뿐만 아니라 문화 전반에 걸쳐 많은 영향을 끼친 마르틴 부버의 대표작이다.

부버는 이 책에서 세상에는 '나와 너'(Ich-Du)의 관계와 '나와 그것'(Ich-Es)의 관계가 존재하는데, 참다운 삶을 살기 위해서는 '나와 너'의 관계를 맺어야 한다고 주장한다. '나와 그것'의 관계는 도구적인 관점에서 세상을 바라보며 대상이 언제든지 대체될 수 있는 일시적이고 기계적인 관계이기 때문이다. 반면 '나와 너'의 관계는 서로가 인격적으로 마주하는 관계로서 무엇과도 대체될 수 없는 유일한 '나'와 대체 불가능한 '너'가 깊은 신뢰 속에서 존재하는 관계이다. 자신의 참다운 내면을 발견하기 위해서라도 '나와 너'의 관계를 맺는 것이 필요하다. 인간은 관계 속에서만 진정한 자아를 찾을 수 있기 때문이다.

한편 부버는 “온갖 참된 삶은 만남”이라고 주장했다. 이와 관련, 그는 인간으로서의 가치와 존엄성을 잃어버리는 현대의 비극은 인간과 인간 사이의 참된 관계와 대화가 상실되었기 때문이라고 진단했다. 그래서 만남과 대화야말로 인간의 삶에 있어서 가장 근원적인 모습이라고 말한다.

이 책에서 부버는 모든 만남의 연장선은 '영원자 너'(하나님)에게 향한다고 했는데, 이것은 유대적 신비주의의 일면을 드러내는 것이라 할 수 있다. 부버에 따르면, 만남은 개인적 경험이나 노력으로 얻어질 수 있는 것이라기보다는 주체와 객체가 분리되지 않은, 마치 신의 은총처럼 선험적으로 주어지는 직관적 판단에 가까운 것이다. 그렇기 때문에 만남은 존재를 있는 그대로 받아들이는 영적 합일을 의미한다.

인간 세계는 '나-너'의 근원어에 바탕을 둔, 참다운 대화가 이루어지는 인격 공동체와 ‘나-그것'의 근원어에 바탕을 둔, 오직 독백만이 이루어지는 집단적 사회, 즉 다른 사람을 자기의 욕망 충족시키기 위한 수단, 곧 '그것'으로밖에는 보지 않는 비인격 공동체로 나눌 수 있다. 이에 부버는 세상을 ‘나와 그것’이 아닌 ‘나와 너’의 관계로 만들자고 호소한다.

참된 관계와 대화가 상실된 오늘의 세상에서 이 책은 우리에게 참된 삶의 가치를 일깨워줄 것이다.

-“부록_마르틴 부버에 관한 이해” 중에서

부버는 우리 문화의 거의 모든 면을 다룬 사상가이다. 그렇기 때문에 그의 사상을 충분히 이해하려면 그의 수많은 저서를 하나하나 읽어가는 수밖에 없다. 그러나 그의 모든 작품은 그 사상 전개에서 이 소책자 『나와 너』에 그 연원을 가지고 있다. 『나와 너』는 그의 다른 작품에 대해 수원지 구실을 하고 있다고나 할까. 『나와 너』 는 논문이라고 하기보다는 일종의 철학적 산문시라고 보아야 한다. 여기서는 명멸하는 영감을 얼싸안은 낯익은 일상적 어휘들이 다투어 되풀이되면서 우리 자신도 모르는 사이에 우리를 심원한 철학적·신학적 사색의 세계로 끌고 들어가 숨을 깊이 쉬게 만든다. 그의 작품의 난해성은 결코 용어 때문이 아니다. 이는 그의 사상이 생의 깊이 있는 체험을 전제로 전개되고 있기 때문이다. 그러므로 박식한 사람에게는 난해하다는 이 작품이, 풍부한 인간 경험을 가진 상식적 지성에게는 잘 이해된다는 데에 이 책의 묘미가 있기도 한 것이다.

인간은 ‘관계’ 속에서 진정한 ‘자아’를 찾을 수 있다.

[실전 고전읽기] 27. 마르틴 부버「나와 너」폭염과 폭우가 번갈아 오가면서 여름 무더위가 한창이다.

위세 등등한 여름 하늘을 지배하는 염제(炎帝)를 피해 한적하게 피서를 즐기고 싶다면 책장 사이로 난 오솔길을 총총히 걸어가 보는 것도 나쁘지 않을 듯하다.

활자의 수풀을 구비구비 지나는 여러 갈래의 오솔길 중에서도 특히 정갈한 느낌이 드는 길을 하나 소개하자면 마르틴 부버의 글이 있다.

사람 얼굴에는 그가 타고난 것과 그가 만들어 온 것들이 함께 균형을 이루고 있는데,마르틴 부버의 사진은 성성한 송충이 눈썹 아래 자리 잡은 고요한 샘물 같은 눈이 항상 많은 이야기를 전달한다.

그의 눈만큼이나 깊고 묵상적인 그의 글을 읽어 보노라면 사나운 여름철 더위도 어느덧 가실 것이다.

마르틴 부버(Martin Buber · 1878~1965)는 오스트리아 빈에서 태어난 유대인 사상가로서,유명한 랍비이자 사업가였던 할아버지 솔로몬 부버의 집에서 어린 시절을 보내면서 유대적 신비주의 유산을 물려받았고,성장해서는 빈,라이프치히,취리히,베를린 대학 등지에서 미술사와 철학을 공부하면서 사상적 기반을 다져 나갔다.

인간의 실존과 종교철학,사회사상 등 다방면에서 적극적인 연구 활동을 했던 마르틴 부버는 '인간 문제'(1948) '유토피아에의 길'(1950) '사회와 국가'(1952) 등을 비롯하여 여러 저서를 남겼지만,무엇보다도 그만의 독특한 고유성을 가장 잘 이해할 수 있는 책이자 여름철 피서를 위한 가장 좋은 선택은 '나와 너(Ich und Du)'이다.

'나와 너'는 제목이 워낙 특이해 우선 표제 하나만으로도 기억에 강하게 남는 책인데,이 책 제목이 곧 그대로 부버 사상의 요체이기도 하다.

부버는 세상에는 '나와 너(I-You)'의 관계와 '나와 그것(I-It)'의 관계가 존재하는데,참다운 삶을 살기 위해서는 '나와 너'의 관계를 맺어야만 한다고 주장하였다.

'나와 그것'의 관계는 도구적인 관점에서 세상을 바라보며 대상이 언제든지 대체될 수 있는 일시적이고 기계적인 관계이다.

그러나 '나와 너'의 관계는 서로가 인격적으로 마주하는 관계로서,무엇과도 바꿔질 수 없는 유일한 '나'와 대체 불가능한 '너'가 깊은 신뢰 속에서 존재한다.

부버는 인간이 자신의 참다운 내면을 발견하기 위해서라도 '나와 너'의 관계를 맺어야 한다고 말한다.

인간은 관계 속에서만 진정한 자아를 찾을 수 있기 때문이다.

'나와 너'의 관계인가 '나와 그것'의 관계인가는 나의 상대방만이 달라지는 차이뿐만 아니라,'나' 또한 본질적으로 다르게 존재한다.

만약 내가 '나와 그것'의 관계를 맺는다면,그 관계는 나에게 있어서조차 도구로서 존재하는 나의 한 단면만 보여주지,나의 참다운 의미를 드러내지 못하기 때문이다.

"사람은 나와 너의 관계를 맺음으로써 너와 더불어 현실에 참여한다. 나는 너와 더불어 현실을 나눠 가짐으로 말미암아 현존적 존재가 된다"고 설파한 부버는 인간은 홀로 존재하는 것이 아니라 관계 안에서 의미를 찾는다고 거듭 강조하였다.

부버의 관계지향적 실존주의 철학은 흔히 '대화 철학'이라는 이름으로 소개되기도 한다.

말 그대로 엄숙한 관계 속에서 이뤄지는 진솔한 대화가 중요하다는 주장을 전개하였기 때문이다.

부버는 '관계'의 중요성을 강조하며,인간 존재와 삶의 의미를 그 안에서 찾고자 하였다.

'모든 참된 삶은 만남'이라고 주장하던 부버는 인간으로서의 가치와 존엄성을 잃어버리는 현대의 비극은 인간과 인간 사이의 참된 관계와 대화가 상실되었기 때문이라고 진단하였다.

그는 참다운 삶은 인격체가 조우하고 교섭하면서 가능하다고 주장하였다.

그리고 그는 모든 만남의 연장선은 '영원자 너(하나님)'에게 향한다고 말하면서 유대적 신비주의의 일면을 드러내기도 하였다.

부버에 의하면,만남은 개인적 경험이나 노력으로 얻어질 수 있는 것이라기보다는 주체와 객체가 분리되지 않은,마치 신의 은총처럼 선험적으로 주어지는 직관적 판단에 가까운 것이다.

만남은 영혼의 한가로움 속에서 존재를 있는 그대로 받아들이는 영적 합일(合一) 또는 고양(高揚)을 의미한다.

"사람과 사람의 관계는 사람과 하나님 관계의 비유적 표현이라고도 말할 수 있다.

그 어느 경우에도 참된 부름은 참된 응답을 얻게 되는 것이다"라는 마르틴 부버의 철학은 시온주의 운동에 적극 참여한 그의 인생 행로와도 연관을 맺고 있다고 평할 수 있다.

프랑크푸르트 대학에서 유대교 철학과 윤리학 교수로 재직하다가 1938년 팔레스타인으로 이주하여 히브리 대학에서 강의하면서 아랍인과 유대인의 상호이해 증진을 위하여 노력했던 부버는 '나와 너'의 대화 철학을 아랍인과 유대인 사이에서도 펼치고자 하였다.

기하급수적으로 늘어난 관계 속에서 수많은 사람들이 우리를 스쳐 지나간다.

하지만 대부분이 '나와 그것'의 관계에 불과하지 부버가 주장하는 '나와 너'의 관계는 드물디 드물다.

하지만 "내가 그의 이름을 불러 주기 전에는 그는 다만 하나의 몸짓에 지나지 않았다. 내가 그의 이름을 불러 주었을 때 그는 나에게로 와서 꽃이 되었다"라는 김춘수 시인의 시구처럼 우리들은 모두,너는 나에게 그리고 나는 너에게 잊혀지지 않는 무엇이 되고 싶은 욕망을 감추고 있을 것이다.

'나와 너(Ich und Du)'의 내용은 우물처럼 깊지만 다행히 책의 분량은 그리 길지 않으니 마르틴 부버의 글을 한번 꼼꼼하게 읽으면서 보내는 휴양의 시간을 권하고 싶다.

☞ 기출 제시문 (서강대학교 2006학년도 정시 논술)

세계는 사람이 취하는 이중적인 태도에 따라서 사람에게 이중적이다.

사람의 태도는 그가 말할 수 있는 근원어의 이중성에 따라서 이중적이다.

근원어는 낱개의 말이 아니고 짝말이다.

근원어의 하나는 '나-너'라는 짝말이다.

또 하나의 근원어는 '나-그것'이라는 짝말이다.

'나',그 자체란 없으며 오직 근원어 '나-너'의 '나'와 근원어 '나-그것'의 '나'가 있을 뿐이다.

사람이 '나'라고 말할 때 그는 그 둘 중의 하나를 생각하고 있다.

그가 '나'라고 말할 때 그가 생각하고 있는 '나'가 거기에 존재한다.

또한 그가 '너' 또는 '그것'이라고 말할 때 위의 두 근원어 중 어느 하나의 '나'가 거기에 존재한다. (…중략…)

정신이 독자적 삶 속에 작용해 들어가는 것은 결코 정신 자체가 아니며,'그것'의 세계를 변화시키는 힘에 의한 것이다.

정신이 자기에게 열려 있는 세계를 향하여 마주 나아가 그 세계에 자기를 바쳐서 세계와 그 세계에 속하여 자기를 구원할 수 있을 때,정신은 참으로 '자기 자신'에 돌아와 있는 것이다.

이와 같은 일은 오늘날 산만하고 약화되고 변질되고 철저하게 모순에 빠진 지성이 다시 정신의 본질,곧 '너'를 말할 수 있는 능력을 가지게 될 때 비로소 이루어진다.

'그것'의 세계에서는 인과율이 무제한으로 지배하고 있다.

감각적으로 지각되는 모든 '물리적'인 사건만이 아니라 또한 자기 경험 안에서 이미 발견되었거나 또는 발견되는 모든 '심리적'인 사건도 필연적으로 인과의 계율로 간주된다.

그 중에서 어떤 목적 설정의 성질을 가진 것으로 간주할 수 있는 사건들까지도 역시 '그것'의 세계에 연속체를 이루는 일부로서 인과율의 지배로부터 자유롭지 않다.

인과율이 '그것'의 세계에서 무한정한 지배력을 갖는다는 것은 자연의 과학적 질서를 위해서 근본적으로 중요하다.

그러나 그것이 사람을 억압하지는 못한다.

왜냐하면 사람이란 '그것'의 세계에만 속박되어 있지 않고,거기에서 벗어나 몇 번이고 되풀이하여 관계의 세계로 들어갈 수 있기 때문이다.

이 관계의 세계에서 '나'와 '너'는 서로 자유롭게 마주 서 있으며,어떠한 인과율에도 얽매이지 않고 물들지 않은 상호 관계에 들어선다.

이 관계의 세계 속에서 사람은 자기의 존재 및 보편적 존재의 자유가 보장되어 있음을 알게 된다.

관계를 알며 '너'의 현존을 아는 사람만이 결단할 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있다.

결단하는 사람만이 자유롭다.

왜냐하면 그는 '너'의 면전에 나아간 것이기 때문이다. (…중략…)

관계의 목적은 관계 자체,곧 '너'와의 접촉이다.

왜냐하면 '너'와의 접촉에 의하여 '너'의 숨결,곧 영원한 삶의 입김이 우리를 스치기 때문이다.

관계 속에 서 있는 사람은 현실에 관여한다.

즉 그는 존재에 그저 맞닿아 있는 것도 아니고,존재 밖에 있는 것도 아니다.

바로 존재에 관여하고 있는 것이다.

모든 현실은 하나의 작용이다.

나는 그것을 내 소유로 삼을 수는 없지만 그 작용에 관여하고 있다.

관여가 없는 곳에는 현실이 없다.

자기 독점이 이루어지는 곳에는 현실이 없다.

관여는 직접적으로 '너'와 접촉하는 것이며,그럴수록 그만큼 더 완전하다.

-마르틴 부버,「나와 너」

The notion of I-Thou was developed by the twentieth-century, Jewish philosopher Martin Buber (February 8, 1878 – June 13, 1965). It appeared in his famous work of the same name I and Thou. The term refers to the primacy of the direct or immediate encounter which occurs between a human person and another being. This other being might be another person, another living or inanimate thing, or even God, which is the Eternal Thou. Buber contrasted this more fundamental relation of I-Thou with the I-It relation which refers to our experience of others. Such experience is our mediated consciousness of them which happens either through our knowledge or practical use of them. Through these two basic notions Buber developed his interpretation of existence as being fundamentally “dialogical” as opposed to "monological."

Philosophical Approach

In I and Thou Martin Buber, like many existential thinkers of the same period, preferred a concrete descriptive approach (similar to certain aspects of phenomenology) as opposed to an abstract, theoretical one. In fact, the original English translator of the text, Ronald Gregor Smith, referred to Buber as “a poet,” and indeed the work I and Thou is filled with striking imagery and suggestive metaphors which attempt to describe the I-Thou encounter rather than explain it. Buber was very much influenced by his Jewish heritage and in particular the narratives of the Torah as well as Hasidic tales. Thus, he favored concrete, historical, and dramatic forms of thinking to logical or systematic arguments. Such an approach, however, often drew sharp criticism from those who thought Buber overly romanticized our subjective or emotional experiences.

Existence as Relation

Buber understands human existence to be a fundamentally relational one. For this reason, one never says “I” in isolation but always in or as some kind of relation. His claim throughout I and Thou is that there are two basic ways we can approach existence, namely, through an I-Thou relation or through an I-It experience. He considers the I-Thou relation to be primary, while the I-It is secondary and derivative. Initially, one might think that an I-Thou relation occurs only between human persons, while the I-It experience occurs only between a person and an inanimate object, such as a rock. But this is not what Buber means. Neither relation depends upon the being to which one is relating, but rather each relation refers to the ontological reality of the “between” which connects (or disconnects) the beings which are relating. While the I-Thou refers to a direct, or immediate (non-mediated) encounter, the I-It refers to an indirect or mediated experience.

I-Thou

In being a direct or immediate encounter the I-Thou relation is one of openness in which the beings are present to one another such that a kind of dialogue takes places. Such a dialogue need not be engaged only in words between human persons but can occur in the silent correspondences between a person and beings in the world such as cats, trees, stones, and ultimately God. Buber describes these encounters as mutual such that what occurs between the I and the Thou is communication and response. This encounter requires a mutual openness where this “primary word” of I-Thou is spoken and then received through the response of one’s whole being. Such a response, though, is not a self-denial where one loses oneself in an immersion into the social or collective whole. Rather Buber describes it as a holding one’s ground within the relation, whereby one becomes the I in allowing the other to be Thou. In this way, then, a meeting takes place, which Buber refers to as the only “real living.”

Buber also explains that the I-Thou encounter cannot be produced at will and by the action of one’s own agency. Rather it is one that occurs spontaneously in the living freedom which exists between beings. Nonetheless, one can obstruct such encounters, by swiftly transferring them into an I-It experience. For Buber, then, one must be vigilant with a readiness to respond to these living encounters whenever and wherever they offer themselves. For this reason, he says, “The Thou meets me through Grace – it is not found by seeking.”

When the I-Thou relation occurs within the encounter between human beings, not only is the other not an “It” for me but also not a “He” or a “She.” For any kind of determination restricts the other within the bounds of my own consciousness or understanding. In contrast, in the I-Thou relation I encounter the Thou in the singularity of his or her own uniqueness that does not reduce to him or her to some kind of category. In this way, I enter the sacredness of the I-Thou relation, a relation which cannot be explained without being reduced to an I-It understanding. Thus, the encounter simply is. Nothing can intervene in the immediacy of the I-Thou relation. For I-Thou is not a means to some object or goal, but a relation of presence involving the whole being of each subject.

I-It

The I-It experience is best understood in contrast to the I-Thou relation. It is a relation in which the I approaches the other not in a direct and living immediacy, but as an object, either to be used or known. Here the I rather than enter into the immediate relation with the other stands over and against it and so analyzes, compares, or manipulates it as a mediated object of my consciousness.

Buber uses an example of a tree and presents five separate ways we might experience it. The first way is to look at the tree as one would a picture. Here one appreciates the color and details through an aesthetic perception. The second way is to experience the tree as movement. The movement includes the flow of the juices through the veins of the tree, the breathing of the leaves, the roots sucking the water, the never-ending activities between the tree, earth and air, and the growth of the tree. The third way is to categorize the tree by its type, and so classify it as species and from there study its essential structures and functions. The fourth way is to reduce it to an expression of law where forces collide and intermingle. Finally, the fifth way is to interpret the tree in mathematical terms, reducing it to formulas which explain its molecular or atomic make-up. In all these ways, though, the tree is approached as an It: something to be understood, known, or experienced in some manner.

Although the I-It relation holds less ontological worth, it is not in itself negative or “bad.” For it is a necessary aspect of our existence that we treat things (sometimes other people) in this way. For such knowledge can be used for practical purposes as well as having various speculative, scientific, or artistic value in our intellectual knowledge or aesthetic experience. Nonetheless, Buber does refer to the inevitable transition of all I-Thou relations into an I-It as a kind of sadness or tragedy. Thus, he says, “without It man cannot live. But he who lives with It alone is not a man.”

Eternal Thou

For Buber the I-Thou relation is ultimately a relation with God or the “eternal Thou.” For this reason his thought has often been termed a “religious-existentialism” and even “mystical.” As with all I-Thou encounters the relation to God must be a direct and immediate one. For this reason, Buber rejects both the “God of the philosophers” whereby God’s existence is proven through logical and abstract proofs and the “God of the theologians” whereby God is known through dogmatic creeds and formulas. For both systematic approaches to God are I-It relations that reduce God to an object which is known and understood. God, however, can only be approached in love, which is a subject-to-subject relation. Like all I-Thou encounters, love is not the experience of an object by a subject; rather it is an encounter in which both subjects mutually share in the immediacy of the relation. Since the ultimate Thou is God, in the eternal I-Thou relation there are no barriers when man relates directly to the infinite God.

Finally, Buber saw the relation to the eternal Thou as the basis for our true humanity. Like other twentieth-century thinkers, Buber was concerned with the scientific and technological forces that can lead to dehumanizing aspects of contemporary culture. The renewal of this primary relation of I-Thou is essential, then, in overcoming these impersonal and destructive forces and in turn to restore our basic humanity. Given his emphasis upon relation, and in particular human relations (to God, other people, and the things in the world), Buber’s philosophy has often been called a philosophical anthropology.