The Story of Art, EH Gombrich, Strange Beginning

“We do not know how art began any more than we know how language started” Gombrich shared. Through the remains of ancient paintings, sculptures, artifacts, ruins we can imagine the different strange beginnings our primitive ancestors once lived and created…. “We call those people ‘primitive’ not because they are simpler than we are — their processes of thought are often more complicated than ours- but because they are closer to the state from which all mankind once emerged” Gombrich clarified.

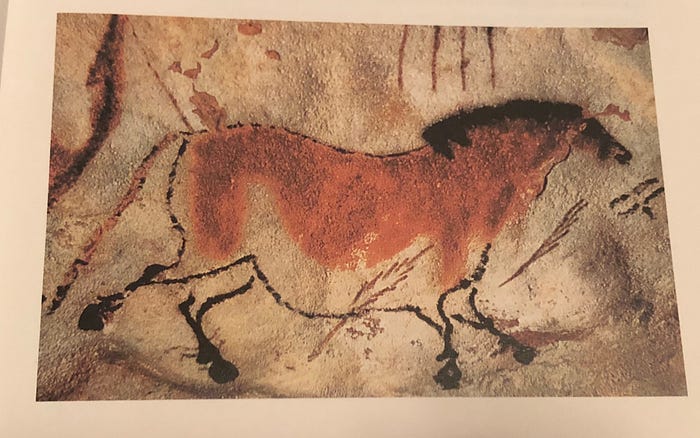

Two of the oldest discovered human paintings includes the picture of a strong, delicious looking bison and a cute chubby horse found in caves of Spain and France ~c. 15,000–10,000BC. I was surprised to learn that “archaeologists refused at first to believe that such vivid and lifelike representation of animals could have been made by men in the Ice Age” — I don’t think they accepted Gombrich’s clarification that primitive people do not mean simpler people. Of course, our ancestors had less technology, tools, and access to today’s encyclopedia of a cumulated world knowledge- but none of that, to me, should hinder their ability in observing the world around them and their capabilities in creating just as beautiful, vivid, and lifelike art as artists do today. I’m not impressed that the paintings are good, I’m impressed they lasted this long!

Many, many dynasties later… we enter the nineteenth century and are still surprised that “some parts of the world primitive artists have developed elaborate systems to represent various figures and totems of their myths in such ornamental fashion,” Gombrich shared. What is interesting to me is that most older artwork from Western and popular civilizations from the point of view of the Western civilization (e.g. Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia) are described as mostly just “ancient”, “great”, or some variation of respect that reflects the expected accomplishments of an impressive civilization of the past. In contrast, indigenous artists or artwork from less popular civilizations (e.g. African, native America) are often labeled as primitive and strange with far lower expectations.

For example, in describing a model of a chieftain’s house of the Haida tribe, Gombrich explains that while “we may see only a jumble of ugly masks, but to the native this pole illustrates an old legend of his tribe. The legend itself may strike us as nearly as odd and incoherent as its representation, but we ought no longer to feel surprised that native ideas differ from ours.”

Here’s the story of the “odd and incoherent” legend as descried by Gombrich:

“ Once there was a young man in the town of Gwais Kun who used to laze about on his bed the whole day till his mother-in-law remarked on it; he felt ashamed, went away and decided to slay a monster which lived in a lake and fed on human and whale. With the help of a fairy bird he made a trap of a tree trunk and dangled two children over it as bait. The monster was caught, the young man dressed in its skin and caught fishes, which he regularly left on his critical mother-in-law’s doorstep. She was so flattered at these unexpected offerings that she thought of herself as a powerful witch. When the young man undeceived her at last, she felt so ashamed that she died.”

Gombrich does ‘praise’ the work by speculating “it is tempting to regard such a work as the product of an odd whim, but to those who made such things this was a solemn undertaking. It took years to cut these huge poles with the primitive tools at the disposal of the natives, and sometimes the whole male population of the village helped in the task. It was to mark and honor the house of a powerful chieftain.”

Imagine seeing strange nineteenth century stories from Western legend such as Hansel and Gretel or even tenth century folk tale like the Little Red Riding Hood as art displayed in Museums too. Imagine those stories became a solemn undertaking that took individual artists and sometimes even whole populations years to recreate into films and other mediums. What if Haida fairy tales are not that different from the fairy tales of the West. What if they are just different creative stories, drawings, carvings, movies… that’s neither too strange that too primitive from what people are still creating today.