하버-보슈법, Haber-Bosch process, 하버법

현대 산업 현장에서 주요하게 사용되는 암모니아 합성 공법이다. 공법을 발명한 프리츠 하버와 카를 보슈의 이름을 따 지었다. 비료 제작에 사용되어 현대 인류 부양에 지대한 공헌을 하고 있다.

인류의 숙원사업

산업혁명 이전의 농경중심사회의 주 관심은 농업생산력 증대에 있었다. 의식주 중에 식량은 가장 절실한 문제로 충분한 식량자원 확보는 인류의 오랜 숙원사업이었다. 농경기술 발전을 통해 증산이 이루어지기는 했으나 기술발전은 더디었고 황무지 개간 등으로는 증산의 한계가 있었다. 결국 곡물 생산량은 인구증가에 미치지 못하여 인류는 항상 굶주림의 고통속에 살아왔으며, 전쟁과 흉년에는 기근으로 인해 아사자가 발생하였다. 이런 문제는 1492년 콜럼버스의 신대륙 탐험이후 아메리카 대륙에서 넘어온 옥수수와 감자 등의 구황작물을 통해 어느정도 해결이 되는 듯했다. 그러나 18세기들어 서서히 인구가 증가하자, 급격한 인구증가는 식량부족으로 인해 재앙을 초래할 수 있다는 맬서스의 경고가 1798년에 발표되기도 했다.

급격한 인구 증가

감자의 신분상승

콜럼버스 시대의 탐험가들에 의해 유럽에 전래된 옥수수 등의 작물들은 인기가 있었다. 그러나 스페인의 잉카 정복자들에 의해 16세기 중후반에 감자가 소개되자 유럽인들은 큰 거부감을 보였다. 유럽인들은 감자의 생김새가 기이했고 번식과 재배방식이 상서롭지 못하다고 여겼다. 나병을 유발한다는 소문까지 퍼지며 관상용이나 가축사료에 사용할뿐 먹지 않았다. 이런 감자는 영국의 곡물공출 정책 등으로 인해 17세기 초반부터 아일랜드인의 주식이 되었고 아일랜드 인구는 폭발적으로 증가했다. 아일랜드를 제외한 유럽인들이 감자를 본격적으로 먹기 시작한 것은 18세기 후반이었다. 7년전쟁을 치루며 감자의 가치를 알게 된 프리드리히 대왕과 프랑스의 농경학자 파르망티에의 노력 덕분이었다. 감자는 전란의 피해가 적고 가뭄에도 강했기에 구황식품으로 점차 귀한 대접을 받기 시작했고, 18세기부터 식품으로 자리잡자 유럽의 인구는 큰폭으로 증가했다.

질소비료의 중요성

독일의 지리학자 훔볼트가 남미 탐험을 마치고 1804년에 유럽으로 돌아온후, 페루의 구아노(guano)를 수입하여 비료로 사용하면 농작물 생산량을 크게 증대시킬수 있다고 주장했으나 아무도 관심을 가지지 않았다. 그러나 1841년에 '농예화학의 아버지'라 평가되는 화학자 리비히가 '식물의 무기 영양론'을 발표하자 상황이 달라졌다. 그는 식물이 공기로부터 얻는 이산화탄소와 뿌리로부터 얻는 질소 화합물과 미네랄을 가지고 성장한다는 사실을 알아냈다. 또한 비료의 필수 성분이자 가장 중요한 성분이 질소라는 것을 밝혔다.

일반적인 축산분료로 만들어진 퇴비보다 구아노 속의 질소와 인의 함량은 월등히 높았다. 건조한 해안지방에서 바다새의 배설물이 오랜세월 응고, 퇴적되며 많은 질소가 농축되어 있기 때문이다. 리비히의 발표이후 유럽인들은 구아노를 수입하기 시작했다. 구아노 속에 있는 질소는 화약을 제조하는데도 필요했기 때문에 구아노의 경제적 가치가 상승하면서 이를 수출하게 된 페루의 경제는 크게 호황을 누렸다.

과학계의 숙제

18세기 중반 8억명이던 세계인구가 19세기 말에 15억 정도로 크게 증가했지만 농업생산성은 인구증가에 비례하여 향상되지 않았다. 적극적으로 식민지를 개척하여 농경지를 확장시켜 나갔으나 한계가 있었다. 맬서스가 《인구론》을 통해 "식량은 산술급수적으로 증가하는 반면 인구는 기하급수적으로 팽창한다"고 주장했는데, 이것이 마치 예언처럼 실현되어 19세기 말 인구는 폭발적으로 증가하였고 인류는 ‘식량부족’이라는 커다란 문제에 봉착했다. 1898년 영국 과학아카데미의 원장인 윌리엄 크룩스는 1930년대쯤 대규모 기아사태가 발생할 것이라고 비관적인 전망을 하며 인류구원의 길은 화학비료 개발에 있다고 강조했다. 또한 의학의 발달로 인구가 급격히 증가했고, 산업혁명으로 농촌인력이 도시로 몰려 식량생산이 감소했다는 사실도 지목했다. 이런 사회적 분위기 속에 화학비료 개발은 당시 과학계의 중요한 과제로 떠올랐다.

화학비료 개발

암모니아 합성

반응식

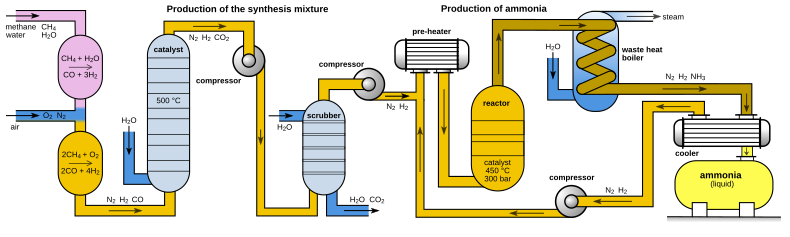

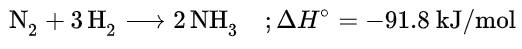

암모니아는 금속 촉매를 통해 다음과 같은 화학반응식으로 생성된다.

그러나, 이 반응은 대기중의 질소가 매우 안정한 물질이기 때문에 고온, 고압의 철 계통의 촉매가 있어야 한다. 촉매를 사용하여 약 200기압, 400~500°C에서 반응이 진행, 암모니아를 만든다. 이를 하버법, 혹은 하버-보슈법이라 한다. 하버는 처음에는 철을 사용했으나 좋은 수득률을 얻는데에는 실패하고, 이후 오스뮴을 사용해 좋은 성과를 얻는다. 현대에는 철에 기반한 촉매를 여전히 사용한다.

이렇게 생성된 암모니아는 질산, 황산과 혼합하여 질산암모늄이나 황산암모늄을 만든다. 이로써 비료를 만들어 식량문제를 해결하였는데, 하버와 보슈는 이 업적으로 하버는 1918년, 보슈는 1931년에 노벨화학상을 수상했다.

Haber-Bosch process

Haber-Bosch process, method of directly synthesizing ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen, developed by the German physical chemist Fritz Haber. He received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918 for this method, which made the manufacture of ammonia economically feasible. The method was translated into a large-scale process using a catalyst and high-pressure methods by Carl Bosch, an industrial chemist who won a Nobel Prize in 1931 jointly with Friedrich Bergius for high-pressure studies.

Haber-Bosch was the first industrial chemical process to use high pressure for a chemical reaction. It directly combines nitrogen from the air with hydrogen under extremely high pressures and moderately high temperatures. A catalyst made mostly from iron enables the reaction to be carried out at a lower temperature than would otherwise be practicable, while the removal of ammonia from the batch as soon as it is formed ensures that an equilibrium favouring product formation is maintained. The lower the temperature and the higher the pressure used, the greater the proportion of ammonia yielded in the mixture. For commercial production, the reaction is carried out at pressures ranging from 200 to 400 atmospheres and at temperatures ranging from 400° to 650° C (750° to 1200° F). The Haber-Bosch process is the most economical for the fixation of nitrogen and with modifications continues in use as one of the basic processes of the chemical industry in the world. See also nitrogen fixation.

Ammonia and amines have a slightly flattened trigonal pyramidal shape with a lone pair of electrons above the nitrogen. In quaternary ammonium ions, this area is occupied by a fourth substituent.

Ammonia and amines have a slightly flattened trigonal pyramidal shape with a lone pair of electrons above the nitrogen. In quaternary ammonium ions, this area is occupied by a fourth substituent.

Uses of ammonia

The major use of ammonia is as a fertilizer. In the United States, it is usually applied directly to the soil from tanks containing the liquefied gas. The ammonia can also be in the form of ammonium salts, such as ammonium nitrate, NH4NO3, ammonium sulfate, (NH4)2SO4, and various ammonium phosphates. Urea, (H2N)2C=O, is the most commonly used source of nitrogen for fertilizer worldwide. Ammonia is also used in the manufacture of commercial explosives (e.g., trinitrotoluene [TNT], nitroglycerin, and nitrocellulose).

In the textile industry, ammonia is used in the manufacture of synthetic fibres, such as nylon and rayon. In addition, it is employed in the dyeing and scouring of cotton, wool, and silk. Ammonia serves as a catalyst in the production of some synthetic resins. More important, it neutralizes acidic by-products of petroleum refining, and in the rubber industry it prevents the coagulation of raw latex during transportation from plantation to factory. Ammonia also finds application in both the ammonia-soda process (also called the Solvay process), a widely used method for producing soda ash, and the Ostwald process, a method for converting ammonia into nitric acid.

Ammonia is used in various metallurgical processes, including the nitriding of alloy sheets to harden their surfaces. Because ammonia can be decomposed easily to yield hydrogen, it is a convenient portable source of atomic hydrogen for welding. In addition, ammonia can absorb substantial amounts of heat from its surroundings (i.e., one gram of ammonia absorbs 327 calories of heat), which makes it useful as a coolant in refrigeration and air-conditioning equipment. Finally, among its minor uses is inclusion in certain household cleansing agents.

Preparation of ammonia

Pure ammonia was first prepared by English physical scientist Joseph Priestley in 1774, and its exact composition was determined by French chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet in 1785. Ammonia is consistently among the top five chemicals produced in the United States. The chief commercial method of producing ammonia is by the Haber-Bosch process, which involves the direct reaction of elemental hydrogen and elemental nitrogen.

N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

This reaction requires the use of a catalyst, high pressure (100–1,000 atmospheres), and elevated temperature (400–550 °C [750–1020 °F]). Actually, the equilibrium between the elements and ammonia favours the formation of ammonia at low temperature, but high temperature is required to achieve a satisfactory rate of ammonia formation. Several different catalysts can be used. Normally the catalyst is iron containing iron oxide. However, both magnesium oxide on aluminum oxide that has been activated by alkali metal oxides and ruthenium on carbon have been employed as catalysts. In the laboratory, ammonia is best synthesized by the hydrolysis of a metal nitride.

Mg3N2 + 6H2O → 2NH3 + 3Mg(OH)2

Physical properties of ammonia

Ammonia is a colourless gas with a sharp, penetrating odour. Its boiling point is −33.35 °C (−28.03 °F), and its freezing point is −77.7 °C (−107.8 °F). It has a high heat of vaporization (23.3 kilojoules per mole at its boiling point) and can be handled as a liquid in thermally insulated containers in the laboratory. (The heat of vaporization of a substance is the number of kilojoules needed to vaporize one mole of the substance with no change in temperature.) The ammonia molecule has a trigonal pyramidal shape with the three hydrogen atoms and an unshared pair of electrons attached to the nitrogen atom. It is a polar molecule and is highly associated because of strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding. The dielectric constant of ammonia (22 at −34 °C [−29 °F]) is lower than that of water (81 at 25 °C [77 °F]), so it is a better solvent for organic materials. However, it is still high enough to allow ammonia to act as a moderately good ionizing solvent. Ammonia also self-ionizes, although less so than does water.

2NH3 ⇌ NH4+ + NH2−

Chemical reactivity of ammonia

The combustion of ammonia proceeds with difficulty but yields nitrogen gas and water.

4NH3 + 3O2 + heat → 2N2 + 6H2O

However, with the use of a catalyst and under the correct conditions of temperature, ammonia reacts with oxygen to produce nitric oxide, NO, which is oxidized to nitrogen dioxide, NO2, and is used in the industrial synthesis of nitric acid.

Ammonia readily dissolves in water with the liberation of heat.

NH3 + H2O ⇌ NH4+ + OH−

These aqueous solutions of ammonia are basic and are sometimes called solutions of ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH). The equilibrium, however, is such that a 1.0-molar solution of NH3 provides only 4.2 millimoles of hydroxide ion. The hydrates NH3 · H2O, 2NH3 · H2O, and NH3 · 2H2O exist and have been shown to consist of ammonia and water molecules linked by intermolecular hydrogen bonds.

Liquid ammonia is used extensively as a nonaqueous solvent. The alkali metals as well as the heavier alkaline-earth metals and even some inner transition metals dissolve in liquid ammonia, producing blue solutions. Physical measurements, including electrical-conductivity studies, provide evidence that this blue colour and electrical current are due to the solvated electron.

metal (dispersed) ⇌ metal(NH3)x ⇌ M+(NH3)x + e−(NH3)y

These solutions are excellent sources of electrons for reducing other chemical species. As the concentration of dissolved metal increases, the solution becomes a deeper blue in colour and finally changes to a copper-coloured solution with a metallic lustre. The electrical conductivity decreases, and there is evidence that the solvated electrons associate to form electron pairs.

2e−(NH3)y ⇌ e2(NH3)y

Most ammonium salts also readily dissolve in liquid ammonia.

Derivatives of ammonia

Two of the more important derivatives of ammonia are hydrazine and hydroxylamine.

Hydrazine

Hydrazine, N2H4, is a molecule in which one hydrogen atom in NH3 is replaced by an ―NH2 group. The pure compound is a colourless liquid that fumes with a slight odour similar to that of ammonia. In many respects it resembles water in its physical properties. It has a melting point of 2 °C (35.6 °F), a boiling point of 113.5 °C (236.3 °F), a high dielectric constant (51.7 at 25 °C [77 °F]), and a density of 1 gram per cubic cm. As with water and ammonia, the principal intermolecular force is hydrogen bonding.

Hydrazine is best prepared by the Raschig process, which involves the reaction of an aqueous alkaline ammonia solution with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl).

2NH3 + NaOCl → N2H4 + NaCl + H2O

This reaction is known to occur in two main steps. Ammonia reacts rapidly and quantitatively with the hypochlorite ion, OCl−, to produce chloramine, NH2Cl, which reacts further with more ammonia and base to produce hydrazine.

NH3 + OCl− → NH2Cl + OH−

NH2Cl + NH3 + NaOH → N2H4 + NaCl + H2O

In this process there is a detrimental reaction that occurs between hydrazine and chloramine and that appears to be catalyzed by heavy metal ions such as Cu2+. Gelatin is added to this process to scavenge these metal ions and suppress the side reaction.

N2H4 + 2NH2Cl → 2NH4Cl + N2

When hydrazine is added to water, two different hydrazinium salts are obtained. N2H5+ salts can be isolated, but N2H62+ salts are normally extensively hydrolyzed.

N2H4 + H2O ⇌ N2H5+ + OH−

N2H5+ + H2O ⇌ N2H62+ + OH−

Hydrazine burns in oxygen to produce nitrogen gas and water, with the liberation of a substantial amount of energy in the form of heat.

N2H4 + O2 → N2 + 2H2O + heat

As a result, the major noncommercial use of this compound (and its methyl derivatives) is as a rocket fuel. Hydrazine and its derivatives have been used as fuels in guided missiles, spacecraft (including the space shuttles), and space launchers. For example, the Apollo program’s Lunar Module was decelerated for landing, and launched from the Moon, by the oxidation of a 1:1 mixture of methyl hydrazine, H3CNHNH2, and 1,1-dimethylhydrazine, (H3C)2NNH2, with liquid dinitrogen tetroxide, N2O4. Three tons of the methyl hydrazine mixture were required for the landing on the Moon, and about one ton was required for the launch from the lunar surface. The major commercial uses of hydrazine are as a blowing agent (to make holes in foam rubber), as a reducing agent, in the synthesis of agricultural and medicinal chemicals, as algicides, fungicides, and insecticides, and as plant growth regulators.

Hydroxylamine

Hydroxylamine, NH2OH, may be thought of as being derived from ammonia by replacement of a hydrogen atom with a hydroxyl group (―OH). The pure compound is a colourless solid that is hygroscopic (rapidly absorbs water) and thermally unstable. It must be stored at 0 °C (32 °F) so that it will not decompose. It melts at 33 °C (91.4 °F), has a density of 1.2 grams per cubic cm at 33 °C, and has a high dielectric constant (ε = 78). Aqueous solutions of hydroxylamine are not as strongly basic as either ammonia or hydrazine. Hydroxylamine can be prepared by a number of reactions. A laboratory synthesis involves the reduction of aqueous potassium nitrite, KNO2, or nitrous acid, HNO2, with the hydrogen sulfite ion, HSO3−. In general, hydroxylamine is stored and used as an aqueous solution or as a salt (for example, NH3OH+NO3−). It is often used in the preparation of oximes.