행복의 측정, 주관적 안녕, subjective well-being

쾌락주의적 입장 (Diener, 1984, 1994)

주관적 안녕’(subjective well-being)_삶에 대한 전반적이고 주관적인 평가

1) 많은 긍정 정서(행복감, 즐거움, 환희감..)를 경험할 수록

2) 적은 부정 정서(우울감, 슬픔, 질투감..)를 경험 할수록

3) 삶의 만족도가 높을 수록

: 개인이 설정한 기준과 비교하여 삶의 상태를 평가하는 의식적이고 인지적인 판단

Diener의 SWB 측정척도가 타당도와 신뢰도는 검증된 측정치들이지만 문항 내용들이 한국인의 행복감을 제대로 담고 있는지에 대해서는 확신하기 어려웠기에 한국인의 정서가 개입될 여지가 있는 행복 측정치를 개발함

SWB의 3가지 요인들(삶의 만족, 긍정정서, 부정정서)를 9문항으로 축약

1) 만족감 측정

① 개인적 : 개인적 성취

② 관계적: 가족, 친구, 동료 등과의 관계

③ 집단적: 자신의 학교, 직장, 동우회 등

2) 긍정적 정서경험

① 고각성 긍정적 정서: 즐거움

② 긍정적 정서: 행복함

③ 저각성 긍정적 정서: 편안함

3) 부정적 정서 경험

① 고각성 부정적 정서: 짜증

② 부정적 정서: 부정적인

저각성 부정적 정서: 무기력한

어떻게 사는 것이 잘 사는 것일까? 행복하다는 것은 어떤 삶의 상태를 의미하는가? 행복한 사람은 어떤 특성을 지니고 있는가? 어떤 나라의 사람들이 가장 행복할까? 이러한 물음에 대한 학문적 관심이 1960년대부터 증대되었다. 국가는 국민 대다수의 행복을 증대시키는 것이 궁극적인 목적이다. 따라서 국가의 발전과 기능 정도를 국민의 행복도에 의해 평가하려는 학문적 시도가 나타나게 되었다. 국가, 계층, 연령, 성별, 종교 등에 따른 집단구성원이 느끼는 삶의 행복감이나 만족도를 측정하려는 사회지표운동(social indicators movement)이 일어나 행복과 관련된 인구 사회학적 요인을 밝히려는 많은 연구가 진행되었다(Duncan, 1969).

그러나 행복감은 개인이 생활 속에서 주관적으로 경험하는 것이기 때문에 인구사회학적 변인은 삶의 만족도에 영향을 주는 일반적인 요인일 뿐 개인의 주관적 행복을 설명하는 데에는 한계가 있다고 지적되었다. 따라서 최근에는 개인의 행복에 영향을 미치는 심리적 요인에 대한 연구가 활발하게 진행되고 있다. 이러한 연구에서는 행복이라는 일상적 용어보다는 주관적 안녕(subjective well-being), 삶의 질(quality of life), 삶의 만족도(life satisfaction)라는 용어를 사용하는 경향이 있다.

주관적 안녕은 가장 널리 사용되고 있는 용어로서 다양하게 정의되고 있으나 정서적 요소와 인지적 요소로 구성되어 있는 것으로 보고 있다(Diener, 1984, 1994). 주관적 안녕의 정서적 요소는 긍정적 정서와 부정적 정서를 말한다. 긍정적 정서와 부정적 정서는 서로 연관되어 있으나 상당히 독립적인 것으로 알려져 있다. 반면, 인지적 요소는 개인이 설정한 기준과 비교하여 삶의 상태를 평가하는 의식적이고 인지적인 판단을 의미하며 삶의 만족도라고 흔히 지칭된다.

주관적 안녕을 구성하는 정서적 요소와 인지적 요소는 서로 밀접한 관계에 있지만 상당히 독립적으로 변화하며 다른 요인과의 관계에서도 차이를 나타낸다. 일반적으로 정서적 반응은 단기적인 상황변화에 대한 직접적인 반응으로서 지속기간이 짧으며 무의식적 동기나 생리적 상태에 의해 영향을 받는 경향이 있다. 반면에 인지적 반응은 보다 장기적인 삶의 상태에 대한 의식적 평가로서 삶의 가치관이나 목표에 의해 영향을 받는다. 이러한 심리적 요소로 구성되는 주관적 안녕은 많은 긍정적 정서와 적은 부정적 정서, 그리고 높은 삶의 만족도를 경험하는 상태로 정의되고 있다. 주관적 안녕의 구성요소를 좀 더 자세하게 제시하면 다음과 같이 요약할 수 있다(Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999).

How do we live well? What kind of life does happiness mean? What characteristics do happy people have? Which countries are the happiest? Academic interest in these questions has increased since the 1960s. The ultimate goal of a country is to increase the happiness of the majority of its citizens. Therefore, academic attempts to evaluate the development and function of a country by the happiness of its citizens have emerged. The social indicators movement, which aims to measure the happiness or satisfaction felt by group members according to country, class, age, gender, religion, etc., has occurred, and many studies have been conducted to identify sociodemographic factors related to happiness (Duncan, 1969). However, since happiness is something that individuals subjectively experience in their lives, it has been pointed out that sociodemographic variables are only general factors that affect life satisfaction and have limitations in explaining an individual's subjective happiness. Therefore, research on psychological factors that affect an individual's happiness has been actively conducted recently. These studies tend to use the terms subjective well-being, quality of life, and life satisfaction rather than the everyday term happiness.

Subjective well-being is the most widely used term and is defined in various ways, but is considered to consist of emotional and cognitive elements (Diener, 1984, 1994). The emotional element of subjective well-being refers to positive and negative emotions. Positive and negative emotions are known to be related to each other but are quite independent. On the other hand, the cognitive element refers to a conscious and cognitive judgment that evaluates the state of one's life by comparing it to a standard set by an individual and is often referred to as life satisfaction.

The emotional and cognitive elements that constitute subjective well-being are closely related to each other but change quite independently and also show differences in their relationship with other factors. In general, emotional responses are direct responses to short-term changes in situations, have a short duration, and tend to be influenced by unconscious motivations or physiological states. On the other hand, cognitive responses are conscious evaluations of the state of one's life in the longer term and are influenced by life values or goals. Subjective well-being, which consists of these psychological factors, is defined as a state in which one experiences many positive emotions, few negative emotions, and high life satisfaction. The components of subjective well-being can be summarized as follows (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999).

Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being (SWB) is the scientific term for happiness and life satisfaction—thinking and feeling that your life is going well, not badly. Scientists rely primarily on self-report surveys to assess the happiness of individuals, but they have validated these scales with other types of measures. People’s levels of subjective well-being are influenced by both internal factors, such as personality and outlook, and external factors, such as the society in which they live. Some of the major determinants of subjective well-being are a person’s inborn temperament, the quality of their social relationships, the societies they live in, and their ability to meet their basic needs. To some degree people adapt to conditions so that over time our circumstances may not influence our happiness as much as one might predict they would. Importantly, researchers have also studied the outcomes of subjective well-being and have found that “happy” people are more likely to be healthier and live longer, to have better social relationships, and to be more productive at work. In other words, people high in subjective well-being seem to be healthier and function more effectively compared to people who are chronically stressed, depressed, or angry. Thus, happiness does not just feel good, but it is good for people and for those around them.

Introduction

If you had only one gift to give your child, what would it be? Happiness? [Image: mynameisharsha,

When people describe what they most want out of life, happiness is almost always on the list, and very frequently it is at the top of the list. When people describe what they want in life for their children, they frequently mention health and wealth, occasionally they mention fame or success—but they almost always mention happiness. People will claim that whether their kids are wealthy and work in some prestigious occupation or not, “I just want my kids to be happy.” Happiness appears to be one of the most important goals for people, if not the most important. But what is it, and how do people get it?

In this module I describe “happiness” or subjective well-being (SWB) as a process—it results from certain internal and external causes, and in turn it influences the way people behave, as well as their physiological states. Thus, high SWB is not just a pleasant outcome but is an important factor in our future success. Because scientists have developed valid ways of measuring “happiness,” they have come in the past decades to know much about its causes and consequences.

Types of Happiness

Philosophers debated the nature of happiness for thousands of years, but scientists have recently discovered that happiness means different things. Three major types of happiness are high life satisfaction, frequent positive feelings, and infrequent negative feelings (Diener, 1984). “Subjective well-being” is the label given by scientists to the various forms of happiness taken together. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

Table 1: Three Types of Subjective Well-Being

You can see in the table that there are different causes of happiness, and that these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. Therefore, there is no single key, no magic wand—high SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). Thus, people who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying.

Some people experience all three elements of happiness—they are very satisfied, enjoy life, and have only a few worries or other unpleasant emotions. Other unfortunate people are missing all three. Most of us also know individuals who have one type of happiness but not another. For example, imagine an elderly person who is completely satisfied with her life—she has done most everything she ever wanted—but is not currently enjoying life that much because of the infirmities of age. There are others who show a different pattern, for example, who really enjoy life but also experience a lot of stress, anger, and worry. And there are those who are having fun, but who are dissatisfied and believe they are wasting their lives. Because there are several components to happiness, each with somewhat different causes, there is no magic single cure-all that creates all forms of SWB. This means that to be happy, individuals must acquire each of the different elements that cause it.

Causes of Subjective Well-Being

There are external influences on people’s happiness—the circumstances in which they live. It is possible for some to be happy living in poverty with ill health, or with a child who has a serious disease, but this is difficult. In contrast, it is easier to be happy if one has supportive family and friends, ample resources to meet one’s needs, and good health. But even here there are exceptions—people who are depressed and unhappy while living in excellent circumstances. Thus, people can be happy or unhappy because of their personalities and the way they think about the world or because of the external circumstances in which they live. People vary in their propensity to happiness—in their personalities and outlook—and this means that knowing their living conditions is not enough to predict happiness.

In the table below are shown internal and external circumstances that influence happiness. There are individual differences in what makes people happy, but the causes in the table are important for most people (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lyubomirsky, 2013; Myers, 1992).

Table 2: Internal and External Causes of Subjective Well-Being

Societal Influences on Happiness

When people consider their own happiness, they tend to think of their relationships, successes and failures, and other personal factors. But a very important influence on how happy people are is the society in which they live. It is easy to forget how important societies and neighborhoods are to people’s happiness or unhappiness. In Figure 1, I present life satisfaction around the world. You can see that some nations, those with the darkest shading on the map, are high in life satisfaction. Others, the lightest shaded areas, are very low. The grey areas in the map are places we could not collect happiness data—they were just too dangerous or inaccessible.

Figure 1

Can you guess what might make some societies happier than others? Much of North America and Europe have relatively high life satisfaction, and much of Africa is low in life satisfaction. For life satisfaction living in an economically developed nation is helpful because when people must struggle to obtain food, shelter, and other basic necessities, they tend to be dissatisfied with lives. However, other factors, such as trusting and being able to count on others, are also crucial to the happiness within nations. Indeed, for enjoying life our relationships with others seem more important than living in a wealthy society. One factor that predicts unhappiness is conflict—individuals in nations with high internal conflict or conflict with neighboring nations tend to experience low SWB.

Money and Happiness

Will money make you happy? A certain level of income is needed to meet our needs, and very poor people are frequently dissatisfied with life (Diener & Seligman, 2004). However, having more and more money has diminishing returns—higher and higher incomes make less and less difference to happiness. Wealthy nations tend to have higher average life satisfaction than poor nations, but the United States has not experienced a rise in life satisfaction over the past decades, even as income has doubled. The goal is to find a level of income that you can live with and earn. Don’t let your aspirations continue to rise so that you always feel poor, no matter how much money you have. Research shows that materialistic people often tend to be less happy, and putting your emphasis on relationships and other areas of life besides just money is a wise strategy. Money can help life satisfaction, but when too many other valuable things are sacrificed to earn a lot of money—such as relationships or taking a less enjoyable job—the pursuit of money can harm happiness.

There are stories of wealthy people who are unhappy and of janitors who are very happy. For instance, a number of extremely wealthy people in South Korea have committed suicide recently, apparently brought down by stress and other negative feelings. On the other hand, there is the hospital janitor who loved her life because she felt that her work in keeping the hospital clean was so important for the patients and nurses. Some millionaires are dissatisfied because they want to be billionaires. Conversely, some people with ordinary incomes are quite happy because they have learned to live within their means and enjoy the less expensive things in life.

It is important to always keep in mind that high materialism seems to lower life satisfaction—valuing money over other things such as relationships can make us dissatisfied. When people think money is more important than everything else, they seem to have a harder time being happy. And unless they make a great deal of money, they are not on average as happy as others. Perhaps in seeking money they sacrifice other important things too much, such as relationships, spirituality, or following their interests. Or it may be that materialists just can never get enough money to fulfill their dreams—they always want more.

To sum up what makes for a happy life, let’s take the example of Monoj, a rickshaw driver in Calcutta. He enjoys life, despite the hardships, and is reasonably satisfied with life. How could he be relatively happy despite his very low income, sometimes even insufficient to buy enough food for his family? The things that make Monoj happy are his family and friends, his religion, and his work, which he finds meaningful. His low income does lower his life satisfaction to some degree, but he finds his children to be very rewarding, and he gets along well with his neighbors. I also suspect that Monoj’s positive temperament and his enjoyment of social relationships help to some degree to overcome his poverty and earn him a place among the happy. However, Monoj would also likely be even more satisfied with life if he had a higher income that allowed more food, better housing, and better medical care for his family.

Manoj, a happy rickshaw driver in Calcutta.

Besides the internal and external factors that influence happiness, there are psychological influences as well—such as our aspirations, social comparisons, and adaptation. People’s aspirations are what they want in life, including income, occupation, marriage, and so forth. If people’s aspirations are high, they will often strive harder, but there is also a risk of them falling short of their aspirations and being dissatisfied. The goal is to have challenging aspirations but also to be able to adapt to what actually happens in life.

One’s outlook and resilience are also always very important to happiness. Every person will have disappointments in life, fail at times, and have problems. Thus, happiness comes not to people who never have problems—there are no such individuals—but to people who are able to bounce back from failures and adapt to disappointments. This is why happiness is never caused just by what happens to us but always includes our outlook on life.

Adaptation to Circumstances

The process of adaptation is important in understanding happiness. When good and bad events occur, people often react strongly at first, but then their reactions adapt over time and they return to their former levels of happiness. For instance, many people are euphoric when they first marry, but over time they grow accustomed to the marriage and are no longer ecstatic. The marriage becomes commonplace and they return to their former level of happiness. Few of us think this will happen to us, but the truth is that it usually does. Some people will be a bit happier even years after marriage, but nobody carries that initial “high” through the years.

People also adapt over time to bad events. However, people take a long time to adapt to certain negative events such as unemployment. People become unhappy when they lose their work, but over time they recover to some extent. But even after a number of years, unemployed individuals sometimes have lower life satisfaction, indicating that they have not completely habituated to the experience. However, there are strong individual differences in adaptation, too. Some people are resilient and bounce back quickly after a bad event, and others are fragile and do not ever fully adapt to the bad event. Do you adapt quickly to bad events and bounce back, or do you continue to dwell on a bad event and let it keep you down?

An example of adaptation to circumstances is shown in Figure 3, which shows the daily moods of “Harry,” a college student who had Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a form of cancer). As can be seen, over the 6-week period when I studied Harry’s moods, they went up and down. A few times his moods dropped into the negative zone below the horizontal blue line. Most of the time Harry’s moods were in the positive zone above the line. But about halfway through the study Harry was told that his cancer was in remission—effectively cured—and his moods on that day spiked way up. But notice that he quickly adapted—the effects of the good news wore off, and Harry adapted back toward where he was before. So even the very best news one can imagine—recovering from cancer—was not enough to give Harry a permanent “high.” Notice too, however, that Harry’s moods averaged a bit higher after cancer remission. Thus, the typical pattern is a strong response to the event, and then a dampening of this joy over time. However, even in the long run, the person might be a bit happier or unhappier than before.

Figure 3. Harry’s Daily Moods

Outcomes of High Subjective Well-Being

Is the state of happiness truly a good thing? Is happiness simply a feel-good state that leaves us unmotivated and ignorant of the world’s problems? Should people strive to be happy, or are they better off to be grumpy but “realistic”? Some have argued that happiness is actually a bad thing, leaving us superficial and uncaring. Most of the evidence so far suggests that happy people are healthier, more sociable, more productive, and better citizens (Diener & Tay, 2012; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Research shows that the happiest individuals are usually very sociable. The table below summarizes some of the major findings.

Table 3: Benefits of Happiness

Although it is beneficial generally to be happy, this does not mean that people should be constantly euphoric. In fact, it is appropriate and helpful sometimes to be sad or to worry. At times a bit of worry mixed with positive feelings makes people more creative. Most successful people in the workplace seem to be those who are mostly positive but sometimes a bit negative. Thus, people need not be a superstar in happiness to be a superstar in life. What is not helpful is to be chronically unhappy. The important question is whether people are satisfied with how happy they are. If you feel mostly positive and satisfied, and yet occasionally worry and feel stressed, this is probably fine as long as you feel comfortable with this level of happiness. If you are a person who is chronically unhappy much of the time, changes are needed, and perhaps professional intervention would help as well.

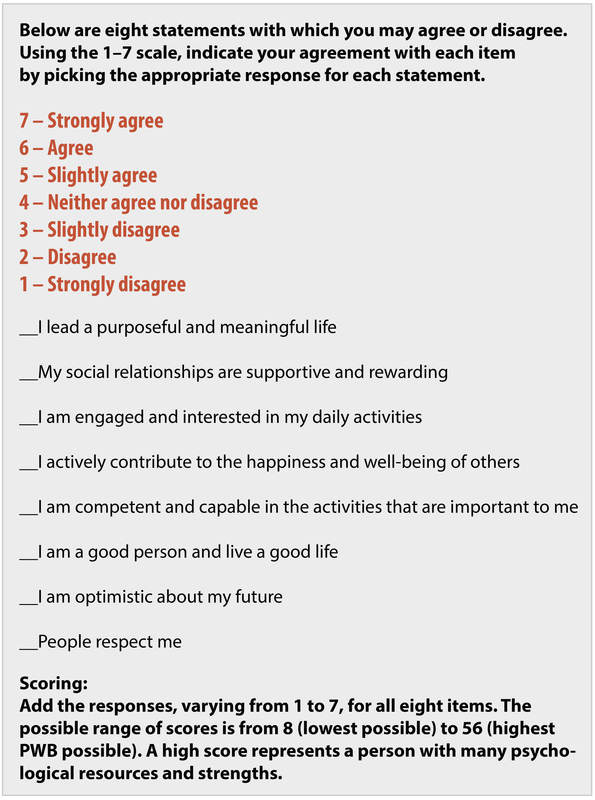

Measuring Happiness

SWB researchers have relied primarily on self-report scales to assess happiness—how people rate their own happiness levels on self-report surveys. People respond to numbered scales to indicate their levels of satisfaction, positive feelings, and lack of negative feelings. You can see where you stand on these scales by going to https://eddiener.com/scales/9 or by filling out the Flourishing Scale below. These measures will give you an idea of what popular scales of happiness are like.

The Flourishing Scale

The self-report scales have proved to be relatively valid (Diener, Inglehart, & Tay, 2012), although people can lie, or fool themselves, or be influenced by their current moods or situational factors. Because the scales are imperfect, well-being scientists also sometimes use biological measures of happiness (e.g., the strength of a person’s immune system, or measuring various brain areas that are associated with greater happiness). Scientists also use reports by family, coworkers, and friends—these people reporting how happy they believe the target person is. Other measures are used as well to help overcome some of the shortcomings of the self-report scales, but most of the field is based on people telling us how happy they are using numbered scales.

There are scales to measure life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 2008), positive and negative feelings, and whether a person is psychologically flourishing (Diener et al., 2009). Flourishing has to do with whether a person feels meaning in life, has close relationships, and feels a sense of mastery over important life activities. You can take the well-being scales created in the Diener laboratory, and let others take them too, because they are free and open for use.

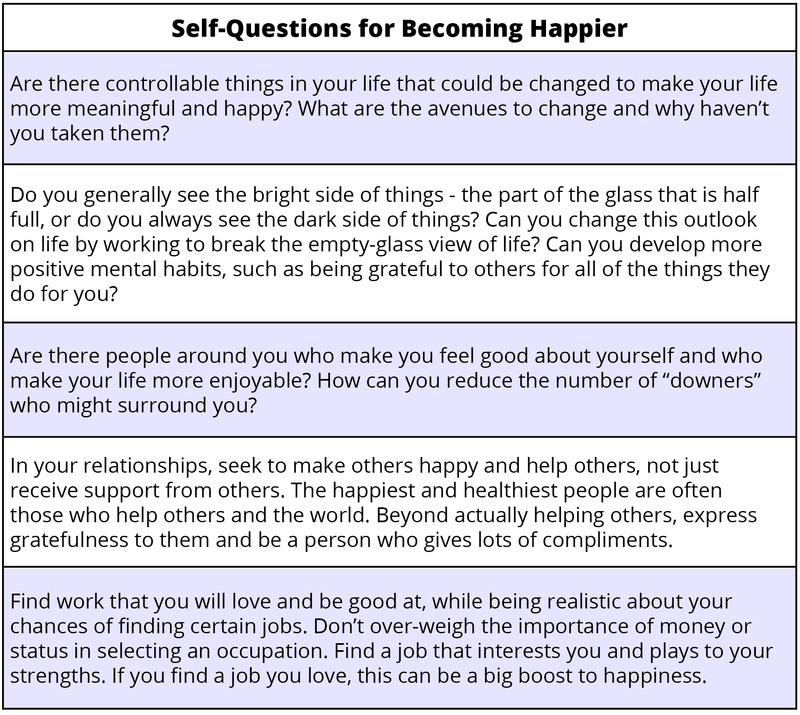

Some Ways to Be Happier

Most people are fairly happy, but many of them also wish they could be a bit more satisfied and enjoy life more. Prescriptions about how to achieve more happiness are often oversimplified because happiness has different components and prescriptions need to be aimed at where each individual needs improvement—one size does not fit all. A person might be strong in one area and deficient in other areas. People with prolonged serious unhappiness might need help from a professional. Thus, recommendations for how to achieve happiness are often appropriate for one person but not for others. With this in mind, I list in Table 4 below some general recommendations for you to be happier (see also Lyubomirsky, 2013):

Table 4: Self-Examination

Outside Resources

Vocabulary

AdaptationThe fact that after people first react to good or bad events, sometimes in a strong way, their feelings and reactions tend to dampen down over time and they return toward their original level of subjective well-being.“Bottom-up” or external causes of happinessSituational factors outside the person that influence his or her subjective well-being, such as good and bad events and circumstances such as health and wealth.HappinessThe popular word for subjective well-being. Scientists sometimes avoid using this term because it can refer to different things, such as feeling good, being satisfied, or even the causes of high subjective well-being.Life satisfactionA person reflects on their life and judges to what degree it is going well, by whatever standards that person thinks are most important for a good life.Negative feelingsUndesirable and unpleasant feelings that people tend to avoid if they can. Moods and emotions such as depression, anger, and worry are examples.Positive feelingsDesirable and pleasant feelings. Moods and emotions such as enjoyment and love are examples.Subjective well-beingThe name that scientists give to happiness—thinking and feeling that our lives are going very well.Subjective well-being scalesSelf-report surveys or questionnaires in which participants indicate their levels of subjective well-being, by responding to items with a number that indicates how well off they feel.“Top-down” or internal causes of happinessThe person’s outlook and habitual response tendencies that influence their happiness—for example, their temperament or optimistic outlook on life.

References

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth. Malden, MA: Wiley/Blackwell.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

- Diener, E., & Tay, L. (2012). The remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. Report of the Well-Being Working Group, Royal Government of Bhutan. Report to the United Nations General Assembly: Well-Being and Happiness: A New Development Paradigm.

- Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2012). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, in press.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). The myths of happiness: What should make you happy, but doesn’t, what shouldn’t make you happy, but does. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

- Myers, D. G. (1992). The pursuit of happiness: Discovering pathways to fulfillment, well-being, and enduring personal joy. New York, NY: Avon.

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.