분노 폭발, 15분만 참아라, 화병(hwa-byung)

화병(hwa-byung)은 수백 가지 정신병 가운데 유일하게 우리나라 말로 만들어진 병명이다. 별로 자랑스럽지 않게도, 한국 사람들이 가진 분노적 기질이 세계적으로 인정받은 결과다. 분노의 부정적 효과는 다양하다. 금세 전파된다. 건강에 좋지 않다. 중독된다. 화가 치민다면 15초만 참아보자. 15번만 규칙적으로 호흡을 해보자. 화를 내야 한다면 스마트하게 내자. 유머를 구사하거나 상대방을 논리적으로 지적하는 방법이 있을 수 있다. 분노의 칼날이 사람에게 향하도록 하지 말고 그의 실수나 잘못된 행동에 초점을 두는 것도 도움이 된다.

업무 현장에서 마음을 경영하는 데 가장 흔하면서 어려운 것이 바로 분노다. 서양 사람들은 스트레스를 받으면 ‘우울하다’ ‘불안하다’고 표현한다. 하지만 필자가 국내에서 연구한 결과에 따르면 우리나라 직장인들이 스트레스를 받을 때 가장 흔하게 나타나는 반응은 바로 ‘분노’다. 한 설문조사에서는 우리나라 직장인 10명 중 8명이 ‘자신을 통제할 수 없을 정도로 감정을 표출한 경험이 있다’고 응답한 바 있다. 요즘 감정경영 또는 감성경영이라는 얘기를 많이 하는데 적어도 국내에서는 분노 문제가 정리돼야만 이런 논의가 실효성을 확보할 수 있을 것으로 보인다.

사실 우리에게 분노(화)는 친숙하다. 정신건강상 병명이 수백 가지인데 그중 유일한 메이드인 코리아 증상이 바로 ‘화병’이다. 그만큼 분노는 우리나라 사람들에게 유독 많이, 그리고 보편적으로 나타나는 현상이다. 분노 반응의 종류도 다양하다. ‘화가 난다’ ‘짜증난다’는 심리적·감정적 반응과 ‘열받는다’ ‘욱 한다’ ‘치밀어 오른다’ 등 몸으로 느끼는 신체적 반응이 있으며 언어폭력이나 인격모욕, 직접적인 적대적·공격적 행동으로도 나타날 수 있다.

분노는 개인의 문제일까, 아니면 조직의 문제일까? 유전적인 문제일까, 아니면 후천적인 양육 환경의 문제일까? 만약 분노가 전혀 없다면 어떻게 될까? 애초에 분노는 왜 생기는 것일까? 분노의 진화적 의미와 기능은 무엇일까?

분노의 기능

원래 분노는 생존을 위해 필요한 것이다. 자신에게 피해를 입힐 가능성이 있는 위험한 자극이나 외부인에게 저항하는 방어적 목적을 가진다. 더 적극적으로 보면 현실에 대한 불만과 분노는 개인과 조직, 사회를 발전시키는 원동력이 된다. 현재에 너무 만족하면 발전이 없다. 부족한 나 자신에 대한 분노가 오뚝이 정신으로 이어진다. 불만족스러운 대우나 한심한 자신의 처지에 화가 나서 와신상담(臥薪嘗膽)을 이룰 수 있다. 나의 노력과 기여를 인정해주지 않는 상대방에 대한 분노 때문에 창업가 정신을 발휘하고 승부근성을 키울 수도 있다. 조직을 관리할 때 리더가 화를 내면 직원들이 그 일에 더 몰두하게 만드는 효과가 있다. 어려운 상황에 처했을 때 분노는 위험을 회피하려는 소극성을 줄이는 역할을 한다. 여기까지가 분노의 순기능이다.

하지만 분노가 순기능을 발휘하려면 일정한 숙성 기간이 필요하다. 그 자리에서 터뜨린 분노는 파괴적이기만 할 뿐 장기적으로는 아무 것도 이룰 수 없다. 즉각적인 분노는 패자의 분노이고 정제된 분노는 승자의 분노다. 사소한 일에 앞뒤 재지 못하고 터뜨린 순간의 분노 때문에 두고두고 후회한 경험이 누구에게나 있을 것이다. 부끄러움을 참고 고백하자면 필자도 예외는 아니다.

그런데 후회를 하고도 사람들은 또 즉각적인 분노의 함정에 빠진다. 이유가 무엇일까. 여기에는 나름대로의 이유가 있다. 분위기가 나쁜 직장이라면 분노의 학습효과가 생긴다. 즉 ‘화를 내니까 내가 원하는 결과가 빨리 나오는구나’ ‘좋게 말해봐야 소용없어. 역시 성질을 내고 다그쳐야 된다니깐. 그러면 바로 말을 듣잖아’ 등의 인식이 팽배하게 된다. 이럴 때 상사의 화는 자기 목적을 빨리 관철시키기 위한 도구로 이용된다. 행동의학적으로 설명하자면 어떤 행동에 대한 보상(reward)이 즉각 따라오면 그 행동이 강화(reinforce)돼서 더 자주 더 강하게 일어난다. 투자한 시간과 노력에 비해 내가 원하는 결과물(직원의 복종이나 명령 수행)이 빨리 나타나면 더 적극적으로 화를 내게 되는 것이다. 따라서 객관적으로 볼 때 감정적으로 화를 심하게 낼 만한 상황이 아닌데도 화를 내고 거칠게 강압적으로 지시하는 일이 반복된다. 화를 내는 행동이 점점 더 당연시되는 것이다.

이렇게 잘못된 행동이 반복되면 분노가 습관으로 굳어진다. 학습된 행동패턴은 몸에 배기 때문에 장소를 가리지 않고 나타난다. 쉽게 목청을 높이고 조바심을 내면서 짜증을 일상화한 직장인은 집에 가서도 배우자나 아이들에게 비슷한 패턴을 반복하기 쉽다. 남을 믿지 못하고 의심이 많은 사람, 불리한 상황이 되면 무조건 남을 탓하거나 고의적이라고 단정하는 사람, 걸핏하면 무시당했다고 열받는 사람, 자기 기준이 엄격한 완벽주의자 등이 습관성 분노 중독에 빠질 위험이 있다. 전 애플 CEO 스티브 잡스는 자기 기준에 못 미치면 불같이 화를 내는 것으로 유명했다. “잡스도 화를 내는데 내가 화를 내는 것이 뭐가 문제냐?”라고 말하는 분은 없으리라 믿는다. 우리는 잡스가 아니다.

분노가 조직에 미치는 역기능은 첫째, 전염성이다. 자기주장과 카리스마가 강한 리더의 분노는 조직에 금방 전파된다. 감정에는 부정적인 감정과 긍정적인 감정이 있는데 부정적인 감정이 퍼지는 속도는 긍정적인 감정의 속도보다 무려 15배가 빠르다. 가령 옆 사람이 깔깔거리고 웃는다고 해서 내 기분이 금방 따라서 좋아지지는 않는다. “저 사람, 왜 저래? 난 바빠 죽을 지경인데 뭐가 저렇게 좋아?” 하며 삐딱하게 볼 수도 있다. 하지만 분노의 한마디는 옆 사람의 기분을 금세 상하게 한다. 게다가 분노의 감정은 물처럼 높은 곳에서 낮은 곳으로 흐른다. 즉 자신보다 약하고 만만한 사람에게 옮기기 쉽다. 그래서 ‘화’는 직장동료나 가족 등 주변 사람들에게 전염된다. 집에서 망친 기분이 회사로 전이되니까 결국 온 조직이 분노의 바다가 될 수 있다.

분노는 세대를 거듭하며 반복되기도 한다. 사회 초년생이었을 때 상사에게 욕먹고 거칠게 훈련받은 사람이 관리자가 되면 감정 조절의 나사가 쉽게 풀린다. 한꺼번에 분노를 폭발시키는 일도 발생한다. 마치 친구들에게 따돌림 당했던 피해자가 나중에 자기보다 약한 아이를 따돌려서 새로운 희생자로 만드는 것처럼 말이다.

둘째, 분노는 건강에 악영향을 미친다. 책상을 치거나 언성을 높이면 당장은 스트레스가 풀릴지 몰라도 심신의 건강에는 좋지 않다. 화가 나면 아드레날린과 같은 스트레스 호르몬이 갑자기 증가한다. 그 결과 혈압이 올라가고 혈관에 응고물질이 증가한다. 화를 잘 내는 사람은 심장병에 잘 걸리고 사망률도 높다. 욱 하고 화를 내면 스트레스 호르몬으로 알려진 코르티솔이 방출된다. 그것이 짧은 순간에 급격히 증가하면 뇌세포를 파괴하는 독성 물질로 작용한다. 특히 코르티솔 과잉 방출은 대뇌의 기억 저장 장치인 해마와 그 주변 세포부터 파괴한다. 그래서 장기적으로 기억력 저하나 가벼운 치매 등 인지기능 저하가 발생할 수 있다. 어떤 사람은 길이 밀리기 시작하면 ‘보나마나 운전 못하는 초보자가 또 길을 엉망으로 만들고 있을 거야’라고 생각한다. 이런 습관 때문에 자기 뇌세포가 파괴되는 줄도 모르고 말이다.

셋째, 분노는 공든 탑을 무너뜨린다. 화를 잘 내는 사람은 열심히 일해서 좋은 평을 듣다가도 한순간의 감정을 조절하지 못하는 탓에 큰 손해를 본다. 문제는 분노에 중독성이 있다는 점이다. 마치 알코올 중독자가 술을 끊지 못하는 것처럼 분노 중독자는 분노를 끊지 못한다. 젊을 때부터 공격적이고 화를 잘 내 온 사람은 중년기에 콜레스테롤 수치가 높다. 미국 듀크대 연구팀에서 실험한 바에 따르면 평소에 화를 얼마나 내 왔는지에 따라 똑같이 화를 내도 몸에서 받는 영향이 달라진다. 연구팀은 실험에 참가한 사람들을 최대한 약 올려서 모두 화를 내도록 만들었다. 참가자 중 평소 화를 잘 내던 사람은 혈압이 훨씬 많이 올라가고 아드레날린 수치도 더 높았다.

분노 관리에서 ‘15’라는 숫자는 중요하다. 한 번 기분 나쁘게 한 것은 열다섯 번 기분 좋게 해야 만회할 수 있다. 부정적인 감정의 말이 긍정적인 감정의 말보다 훨씬 세기 때문이다.

분노의 원인

조직에서 흔히 나타나는 분노 현상을 원인별로 분석해보면 다음과 같다.

첫째, 인정 욕구가 좌절됐을 때다. 사람은 누구나 자기보다 강하고 권위 있는 존재에게 자신의 가치를 인정받고 싶어 한다. 지극히 자연스러운 욕구다. 하지만 다른 사람이 나의 기대만큼 인정 욕구를 늘 채워주기는 불가능하다. 인정 욕구가 채워지지 않을 때, 기대가 클수록 더 분노가 생긴다.

공자의 <논어(論語)> 첫 페이지를 열면 학이(學而) 편이 나오는데 세 번째 문장 “인부지이불온이면 불역군자호아(人不知而不慍이면不亦君子乎아)”가 바로 이런 경우를 다루고 있다. 필자가 정신의학적 해석을 덧붙여 의역하자면 다음과 같다. “남이 알아주지 않는 것이 반가운 일은 아니지만 (내가 성심을 다하고 있음을 하늘이 알고 내 자신이 알기에) 남을 원망하거나 토라지거나 성내지 않는다면 내 마음이 꼬이지 않고 편안하니 이것 또한 군자답지 않은가.” 사실 <논어>에는 규범적이며 이성적인 표현이 많고 인간의 감정을 다루는 단어는 많지 않다. 그런데 학이 편에 나오는 3개의 감정 중 하나가 성낼 온(慍)이다. 이것은 인정받지 못했을 때 느끼는 분노가 보편적인 현상임을 뜻한다. 군자가 되려는 사람일수록 조직(사회)에서 뭔가 역할을 하고 싶은 기대가 크고 자기 실력을 인정받고 싶지 않겠는가. 이 단계를 성숙하게 이겨내야만 군자가 된다는 뜻이니 분노 관리에 많은 시사점을 주는 구절이라고 할 수 있다.

유난히 질투가 강하고 남에게 인정받고 싶은 욕구가 강한 사람, 어렸을 때 가정에서 충분히 인정받지 못했고 지나치게 높고 엄격한 기대를 받고 자란 사람, 상사와 부하 중간에 끼어서 어느 쪽에서도 마음 편하게 인정받지 못하는 소위 ‘샌드위치 관리자’ 등은 인정받지 못했을 때 분노를 더 잘 느낄 수 있다.

가령 마음속에 인정받고 싶은 내면 욕구가 강한 직원이 있는데 그의 행동을 상사가 헤아리지 못한다면 문제가 된다. 새로 부임한 상사와 가까워지려고 상사의 기념일까지 챙길 정도로 노력한 직원이 있다고 하자. 내심 상사에게 좋은 평가를 받을 것으로 기대하며 최선을 다했다. 하지만 돌아온 것은 “잘했다”는 칭찬이 아닌 “뭐 그리 여유가 있어서 이런 것까지 챙기냐. 그 시간에 일이나 더 잘하지”라는 핀잔이었다. 인정받고 싶은 심리가 좌절된 이 직원은 분노할 수밖에 없었다. 인정받고 싶어 하는 조직원이 있다면 그 심리를 이해해주고 반복된 좌절을 맛보지 않게 해야 한다. 인정받고 싶은 마음이 강한지 유심히 살펴보고 열심히 했을 때는 즉각적인 칭찬과 피드백을 줘야 한다.

직원의 성격에 따라 차별적인 분노 관리도 필요하다. 처음 만난 사람과도 잘 어울리는 성격을 가진 사람은 사람들과의 갈등을 싫어한다. 남과 부딪치기 싫으니까 먼저 인사도 하고 자신을 낮추기도 한다. 그런데 성격이 좋으니 맷집도 세겠지 하면서 직설적으로 말하고 화를 내면 오히려 부작용이 생긴다. 친화성이 좋을수록 야단을 맞았을 때 더 분노를 느끼고 칭찬을 받으면 일을 더 잘하는 경향이 있기 때문이다. 이런 사람은 ‘나를 알아주는 구나’와 같은 인정 욕구에 민감하다.

둘째, 탈억제성 분노다. 평소 억제돼 있다가 갑자기 폭발하는 분노다. 평소에는 얌전하던 사람이 한 번 화나면 무섭다. 극심한 감정 폭발은 마음속의 억제하는 아이가 통제력을 상실했을 때 일어난다. 평소 어른스럽게 행동하려고 자신의 욕구를 계속 억압하던 아이가 어느 순간 화산이 폭발하듯 갑자기 감정을 분출하는 것이다. 자신이 어떤 감정 상태인지 잘 모르거나 무시했다가 감당하지 못하고 터질 때도 있다. 감정억제불능증과 감정억제에 대해서는 DBR 144호에 실렸던 스페셜 리포트 01 감성리더십 편에서 다뤘으므로 간략하게만 설명한다.

셋째, 뇌가 감정의 과부하에 걸려서 분노성 기억상실을 겪는 경우다. 얼마 전 어느 대기업 인사부서에서 일하던 분이 부서장 때문에 회사를 그만두고 싶다고 하소연했다. 부서장의 종잡을 수 없는 성격 때문이었는데 평소에는 온순하고 냉정해 보이다가도 기분이 좋지 않은 날에는 무조건 소리부터 지르고 본다는 것이었다. 부하 직원이 사소한 잘못이라도 저지른 날에는 어떻게 사람을 앞에 두고 저럴 수 있나 싶을 정도로 독설을 퍼부어서 회사를 떠나는 직원이 있을 정도라고 했다. 일정은 촉박한데 부하 직원이 잘 따라주지 않으면 화가 날 수도 있다. 그러나 사례의 부서장처럼 감정을 제어하지 못하고 이성을 잃을 정도로 화를 내면 조직원들은 이런 상사와 합심할 수가 없다.

욱 하는 감정, 그러니까 급격하게 흥분하는 ‘감정적 과부하 상태’에 있는 사람들은 대개 일시적으로나마 ‘분노성 기억상실’을 경험한다. 분노성 기억상실이란 흥분했을 때 자신이 했던 말이나 행동을 자세하게 기억하지 못하는 것이다. 기억의 정확성도 떨어지고 ‘그런 뜻이 아니라 이런 뜻이었다’고 자의적으로 해석하기도 한다.

분노 호르몬이 과잉 방출되면 대뇌는 해마와 기억력 전체에 피해가 가지 않도록 보호하기 위해 일단 기억 저장장치를 차단한다. 불이 나면 방화문을 내려서 불길이 퍼지지 않도록 차단하는 것과 같은 원리다. 그래서 일종의 기억상실 현상이 생긴다. 화가 났던 이유나 자기 행동을 전혀 기억하지 못하고 나중에 “내가 정말 그랬나?”며 반문하거나 “내가 그럴 리 없다”며 우기는 일도 일어난다.

스마트하게 화내는 법

“화를 내야 하나? 아니면 참아야 하나?” 필자에게 묻는 가장 흔한 질문이다. 결론부터 말하면 화는 내지도 말고, 참지도 말고, 그저 ‘느끼고 바라보며 지나가기를 기다리면’ 된다. 성인(聖人)이나 도인(道人)이 아닌 이상 ‘화’라는 감정 자체가 생기지 않을 수는 없다. 아니, 아마 성인이나 도인조차 욱 하고 화가 치밀 때가 많을 것이다. 다만 그 화를 잘 다룰 수 있을 뿐이다.

감정이 쌓이면 어디론가 나가야 한다. 댐에 물이 가득 차면 넘치거나 댐을 무너뜨리게 된다. 감정의 흐름도 너무 막으면 참다가 화병이 난다. 그러니 좋은 물길을 내서 잘 흘러나가도록 해야 한다. 댐의 물을 잘 조절하면 그 물이 에너지도 만들고 풍년을 이룰 수 있다.

분노 감정을 방출하는 방법으로는 운동이 제일이다. 운동 중에도 격렬한 운동이 좋다. 실내보다는 실외 운동이 좋다. 자연환경이 제공하는 다양한 시각적·청각적 자극이 주의를 분산시킨다. 주의가 분산돼야 분노에 꽂힌 마음을 다른 곳으로 돌리기 쉽다. 명상도 좋다. 그런데 초보자는 화가 났을 때 명상이 잘되지 않는다. 잡다한 생각이 많이 들기 때문이다. 이럴 때는 몸을 쓰는 활동을 하는 것이 좋다. 이를테면 단순한 명상보다는 요가가 좋다.

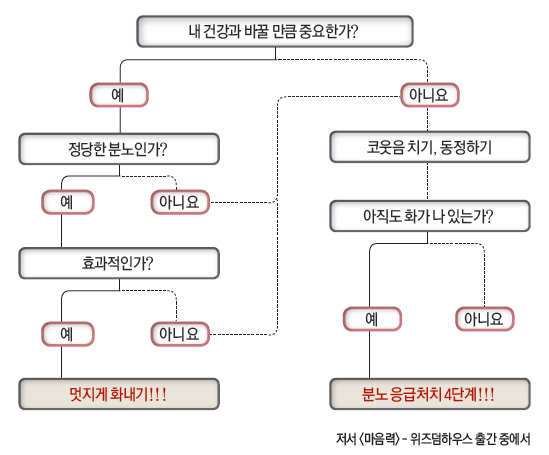

그림 1분노 해결 지도

분노가 생길 때는 세 가지 질문을 통해 화난 감정에서 벗어나도록 노력한다. 첫째, 이 상황이 내 건강과 바꿀 만큼 중요한지 자문한다. 열이 오른다 싶으면 일단 주문을 외운다. ‘화 잘 내면 일찍 죽는다’ ‘화는 내 뇌와 심장을 해친다’. 이런 말들을 머릿속에 넣고 되새긴다. 이 일이 내 건강과 바꿀 만큼 중요한 일인가? 내 뇌를 쪼그라들게 하고 심장에 무리를 주더라도 화를 내야 할 상황인가?

둘째, 이 분노가 정당한가? 사소한 일에 예민하게 구는 것은 아닌가? 누가 봐도 명분이 있고 의로운 분노인가를 자문한다.

셋째, 화내는 것이 문제 해결에 효과적인지, 대안은 없는지, 이것이 목적을 이루기에 가장 좋은 방법인지 자문한다. 대개는 웃으면서 뜻을 전달하는 것이 목적 달성에 가장 효과적이다. 화를 내는 것이 문제 해결에 얼마나 도움이 될지, 내게 어떤 이득과 손실을 가져다줄 것인지, 어떻게 하는 것이 내게 가장 유리한 행동인지 따져보자.

이상의 세 가지 질문에 모두 ‘네’라면 스마트하게 화를 낸다. 스마트한 분노 표현법은 첫째, 유머를 구사한다. “내가 방심할까봐 신경 쓸 일을 많이 만들어주는군” “관심을 더 가져달라고 하는 거지?” “나를 천사로 만들려고 애쓰는 사람 참 많네” 이렇게 웃으면서 아예 상대를 칭찬하거나 유머를 구사하는 것이 스마트한 분노 관리다. 분위기를 망치지 않으면서도 핵심을 전달할 수 있는 방법이다.

둘째, 논리적으로 지적한다. 정 화가 나서 한 방 먹이고 싶으면 아주 침착하게 상대의 문제를 자세히 관찰한 뒤, 감정을 싣지 않고 있는 그대로를 지적한다. “그러니까 ∼란 얘기네요. 그렇게 되면 누가 들어도 제가 억울하다고 보겠네요”라는 식이다.

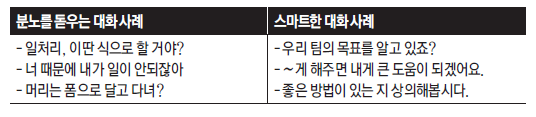

셋째, 담백하게 핵심을 말한다. 좋지 않은 일이나 불편한 이야기를 할 때는 내가 느끼기엔 이러저러하다고 표현한다. 그러면 상대를 공격하지 않고도 정중하게 내가 원하는 바를 전달할 수 있다. 반면 잘된 일은 “당신 덕분에 잘됐다”고 말한다. <표1>을 참고해서 실제 대화를 연습해보라.

표 1분노를 스마트하게 표현하는 방법

넷째, 분노의 대상을 ‘사람’으로 하지 않고 그의 실수나 잘못된 ‘행동’으로 삼는다. 이렇게 하면 화가 난 이유가 명확해지기 때문에 “앞으로는 이 부분에 주의하세요” 등 객관적인 지시를 내릴 수 있다. 상대방도 내가 화를 내는 이유와 자신이 잘못한 점을 정확히 이해할 수 있다. 누군가 잘못을 저질렀을 때 그 사람을 비난하지 말고 구체적인 행동만 지적해야 한다.

위와 같은 방법들을 써도 분노가 가라앉지 않으면 비웃거나 동정한다. 기분은 나쁘지만 그다지 중요하지 않은 일이라면 코웃음을 치거나 혼잣말로 상대방을 동정하면 된다. “거의 인간문화재로군” “평범한 성격은 아니야. 연구 대상으로 삼아야겠는 걸” 등. 통 크게 비웃고 넘겨 버린다. 또는 “에이 불쌍한 녀석!” 하며 동정한다. 상대에 대한 기대를 낮추는 것도 좋은 방법이다. 화를 내는 이유는 대부분 다른 사람에게 거는 기대가 크기 때문이다. 실망은 분노를 만든다. 기대를 하지 않으면 화나는 일이 절반으로 줄어든다.

그래도 조절이 되지 않고 폭발하려고 한다면 응급처치가 필요하다. 일단 그 자리를 피한다. 그게 어려우면 시선을 돌려서 분노의 대상을 정면으로 보지 않고 옆으로 향한다. 잠시 눈을 감아도 좋다.

화가 날 때는 순간적으로 욱 하면서 분노 호르몬이 급상승한다. 분노 호르몬은 15초면 정점을 찍고 분해되기 시작한다. 15분이 지나면 거의 사라진다. 그런데 왜 계속 화가 나는가. 사건 자체가 워낙 크기 때문일 수도 있지만 다수의 많은 경우는 그 일을 두고두고 되씹기 때문이다. 분노의 호르몬이 사라지기 전에 그 일을 다시 떠올리거나 그 사람을 다시 보기 때문에 분노 호르몬이 다시 피크를 향해 올라가는 것이다. 시비가 붙은 자리를 일단 피하고 시야에 들어오지 않으면 대개 15분 정도면 감정의 파도가 지나간다. 기다리는 시간이 지루하다면 눈을 살짝 감고 15번만 규칙적으로 심호흡을 하자. 그러면 자연스럽게 분노의 파도가 지나갈 것이다.

분노 관리에서 ‘15’라는 숫자는 중요하다. 한 번 기분 나쁘게 한 것은 열다섯 번 기분 좋게 해야 만회할 수 있다. 부정적인 감정의 말이 긍정적인 감정의 말보다 훨씬 세기 때문이다. 리더가 직원들의 사기 진작을 위해 좋은 말을 아무리 많이 했더라도 한 번 싫은 소리를 하면 말짱 도루묵이 된다. 직원들은 예전에 들었던 좋은 말은 까맣게 잊고 기분 나쁜 말만 기억한다. 이를 최종정보효과(recency effect)라고 한다. 따라서 15번 기분 좋게 해주는 것보다는 한 번 기분 망치게 할 일을 피하는 편이 낫다.

열심히 애를 썼는데 남에게 인정받지 못하면 화가 난다. 남을 사심 없이 도와줬는데 고마워하기는커녕 배신을 당했다면 불같이 화가 치민다. 당연하다. 이럴 때는 열심히 화를 내자. 그러나 금방 사라질 분노가 아니라 창조와 성숙으로 이어질 분노를 발휘하자. 당장은 15초 참고, 15번 심호흡하고, 15분간 기다리면서 궁극적인 결과를 생각하자.

Hwa-Byung: The “Han” Blessed Illness

Abstract: Hwa-byung (HB) is a Korean culture-bound illness that includes symptoms of insomnia, depression, and somatization in the lower abdomen. This illness is unique in that it is found mostly, but certainly not only, in middle-aged Korean females. Previously, the research approach to HB has been predominantly sociological and focused on middle-aged females. Consequently, the cultural significance of HB has been understood in relation to female gender roles and patriarchal social structure. However, by analyzing online narratives of HB from the Korean website Naver, the current cultural significance of HB can be described using the Korean emotion of “han.” The online narratives suggest that HB is not just a response to gender inequality, but also to social concerns of different populations, including young men. Learning more about the cultural significance of HB will facilitate the communication between HB patients and clinicians.

“Clinicians and scientists will perhaps acknowledge that reading novels and poems might contribute to one’s being a well-rounded person, but probably wouldn’t contribute much to the design of an experiment nor help a surgeon perform a triple bypass, even if the patient happens to be an English professor.”

—Lennard Davis and David Morris, “Biocultures Manifesto”

As illustrated by Lennard Davis and David Morris’s analogy, it is very common to conceptualize culture and biology as two polar entities that are incapable of interacting with each other, much like oil and water. In the same context, it is equally easy to categorize illnesses only as biological entities. In fact, even in the case of mental illnesses such as depression, recent research has been focused heavily on neuroscience. As such, the current research has strived to classify all illnesses as biological phenomena, explained with hormones, viruses, bacteria, and specific parts of the human anatomy. However, the connection between biology and culture does exist. Illnesses have both inextricable biological and cultural aspects that have been focused and researched by many. For instance, bioethicists try to understand how cultural values affect medical choices; the medical educators study how narratives affect therapies, and the list goes on (Davis and Morris 413). Judy Segal, a scholar of health rhetoric, claims it is impossible to separate the cultural aspect and the biological aspect of a disease because not only do people tell narratives of diseases but also the narratives of diseases tell a story about the people (10). This approach to illness as both a cultural and a biological phenomenon is called a “biocultural” approach and it helps understand illnesses beyond the scope of science.

With this connection between culture and disease in mind, one category of illnesses that highlight this connection is culture-bound illness. Culture-bound illnesses are illnesses that occur specifically in certain cultures. One notable example of culture-bound illness is hwa-byung (HB). HB is a Korean mental illness where the patients experience symptoms of depression and insomnia along with somatization in their abdomen (Lin 107). Though there is some controversy as to whether the disease should be instead classified as a subset of major depressive disorder, HB is still considered as a distinct illness due to its characteristic differences from depression. Whereas depression often induces an impulse for suicide, HB has not been found with the same effect and, in fact, found in some cases to give the patients the will to live (Kim 497). Also, HB has a unique set of symptoms such as shortened temper, an increase in talkativeness, and somatization in the form of heat (Kim 497). The most important distinction of HB is that it is associated with building up of anger that generally develops over a long time (Kim 497). In addition, HB is claimed to be somewhat common in Korea, affecting approximately 5% of the general population (Kim 497).

Due to such prominence and uniqueness, sociological and statistical research has been conducted to gain a better understanding of HB. In their article, “Hwa-byung Among Middle-Aged Korean Women: Family Relationships, Gender-Role Attitudes, and Self-Esteem,” Kim and colleagues collect surveys from 395 women who are aged over forty and recruited from the four major metropolitan cities of Korea (Seoul, Incheon, Daejon, and Busan). The paper analyzes the causes of HB in middle-aged Korean women, based on their outcomes, and calls for further research on the effect of family relationship problems and gender roles on HB. Similarly, other sociological research on HB has been conducted to expand the understanding of HB. “Gender Differences in Factors Affecting Hwa-byung Symptoms with Middle-age People,” by Kim and Lee, takes a similar approach to subjects that included men as well as women and “A Review of the Korean Cultural Syndrome Hwa-byung: Suggestions for Theory and Intervention,” by Choi and colleagues, provides a new sociological model to studying HB. These sociological approaches to HB are useful methods for enhancing our understanding of the illness. However, by analyzing contemporary online discourse about HB, we can see how HB “tells a story” about Koreans. Analyzing these stories will lead to fuller understanding of the cultural aspect of HB.

Most of the current research focuses on HB as a product of patriarchal social structure and gender inequality. For instance, in their article, “Hwa-byung Among Middle-Aged Korean Women: Family Relationships, Gender-Role Attitudes, and Self-Esteem,” Kim and her colleagues survey 395 Korean women aged forty years or over, from four metropolitan cities of Korea (500-501). From the analysis of their results, Kim and colleagues claim the main causes of HB in middle-aged women to be family conflicts and their social roles as mother and wife (506). Also, in “A Review of the Korean Cultural Syndrome Hwa-byung: Suggestions for Theory and Intervention,” Lee claims the cause of HB to be the patriarchal social structure: “Hwa-byung is the syndrome that is fundamentally associated with the Korean traditional male dominant culture and the patriarchal social system” (60). The similarity between these articles is that they identify gender roles and Korean features of patriarchal social structure, such as marital conflicts with in-laws, to be the main cause of HB (Lee 60, Kim 498). In these manners, the papers of the past have mostly implied HB to be an expression of the gender inequality that has been faced by Korean women.

It is undeniably true that part of HB’s cultural significance is its representation of gender inequality and familial structure that has manifested in Korean culture throughout history. However, it is also important to note that the cultural significance of HB is not limited to these few particular social issues, though it appears so in many papers. In fact, a fundamental issue with this implication is that this explanation is applicable to only the female patients. For the male patients, the cultural experience of their HB could not be formed by the patriarchal social structure. This issue arises from the fact that previous research is lacking on the recently increased numbers of male HB patients. Analyzing the online HB narratives in the context of the Korean emotion “han” reveals the cultural significance of HB as a representation of social issues that reflect the male patients and the consequent change in its cultural significance. By using the Korean emotion of “han” and taking a biocultural approach to HB, it is evident that HB is not tied only to gender inequality but can also be a response to social concerns that affect men, such as military service, isolation, and hostile working environments.

Han

To understand the cultural significance of HB, it is useful to understand its relationship with the emotion of “han,” as suggested by Hwang in his article, “A Study of Hwa-Byung in Korean Society: Narcissistic/Masochistic Self-disorder and Christian Conversion.” “Han” is a unique Korean emotion that cannot be directly translated to a corresponding word in English or many other languages, much like “schadenfreude” or “weltschmerz” in German. Although varying definitions of “han” exist, the definition of “han” worked with in this paper will be that of Young Hak Hyun, who defined it as “a sense of unresolved resentment against injustice suffered, a sense of helplessness because of the over-whelming circumstances, a feeling of total abandonment a feeling of acute pain of sorrow in one’s guts and bowels making the whole body writhe and wriggle, and an obstinate urge to take revenge and to right the wrong—All these to a greater or lesser degree in combination” (Hwang 32). Comparing this definition with the description of HB given in the introduction, there are various connections that can be drawn between “han” and HB. The “resentment,” “sense of helplessness,” and “urge to take revenge” that defines “han” can be generalized as a form of anger, which may be a part of the piled-up anger that is said to trigger HB. Also, the metaphorical description of “a feeling of acute pain of sorrow in one’s guts and bowels making the whole body writhe and wriggle” is represented verbatim in the somatization symptoms of HB. With these striking similarities, it is evident that there may be a close connection between HB and “han.” In fact, Hwang defines the relationship of HB and “han” to be the following: “the term ‘Han’ refers to the various kinds of emotional states of mind which result from experiencing Han-full (heart breaking) incidents, ‘Hwa-Byung’ refers to the psychiatric term designating a psychosomatic illness caused by Han-full incidents” (35). In other words, “han” can be perceived as the emotion that can be felt from being heart-broken, angry and vengeful that, if accumulated too much, may cause HB in an individual.

Hwa-byung (HB) in Narratives

Although the relationship between HB and “han” already seems somewhat evident, the relationship between the two becomes more definite through the analysis of HB narratives found online. “Han” appears in various forms and emphasis in these HB narratives. Furthermore, associating HB with “han” facilitates the understanding of the cultural significance of HB beyond gender inequality. Upon analyzing the narratives of HB in the context of “han,” HB seems to reflect the major issues of different social groups in Korea, such as hardships in Korean national service, isolation, and hostile working environments.

In contrast to the gender inequality explanation of HB, HB narratives by young males tend to contain some form of “han” against the national service. For instance, in one anonymous online narrative by an anonymous Korean male HB patient in the Korean website Naver Knowledge-in, the author writes his personal account of his life with HB and reveals his “han” towards the Korean military. Naver KnowledgeiN is a very popular website sponsored by a major Korean portal called Naver that often features personal questions or stories to which the author feels the need for replies. While posts to Naver KnowledgeiN can’t be considered a reliable source of accurate information, they do offer insight into how the current generation of Koreans thinks and talks about HB. In this particular narrative, the anonymous male writer in his twenties shares his personal life experience as a HB patient. In this narrative, the man confesses he has had some temper control issues since childhood due to the bad relationship between his parents. Moreover, the man also admits to being subject to peer pressure due to his short temper. However, the man claims his symptoms had worsened and developed into HB after his national service duties in Korea. His words become especially emotional when he starts talking about the national service. The writer claims, “Because of the strict hierarchical structure of the military, I couldn’t complain or express my anger to anyone and had to obey my superior’s commands, regardless of how unjust or how old he was. [These things] were exactly what I was afraid of before I went to the military… and things turned out just as I had expected…. [My heart tells me] that locating every single one of those superiors and killing every single one of them should cure my HB, but I can’t.”1 From these words, the “han” of the man can be identified. The feelings of injustice and the hierarchical structure that forced him to suppress his emotions are revealed through the author’s sense of helplessness in his tone and sentence structure. Also, his rather frightening desire for revenge, along with his sense of helplessness, is an essential part of “han.” Therefore, it can be seen that the man blames the emotion of “han” that he has felt during his national service duty for his worsened symptoms of HB. Moreover, similar observations can be made in other narratives about HB. Many young men have posted narratives about HB identifying national service as the major source of their symptoms and indicating similar emotions of injustice, vengeance, and anger: “A guy in the military always caused anger in my body to rise”5; “Sometimes I even dream about getting my revenge. My biggest mistake was not taking my revenge before I left the military.”6 Hence, from the patterns in these narratives, it can be seen that these young, male HB narratives tell us a story about their writers; the narratives seek to share and represent their writer’s discontent with the national service, not gender inequality.

Isolation is another common issue that frequently appears in online narratives of HB. In another HB narrative from an anonymous but apparently male writer who claims that he has had HB for seven years since high school, the writer blames the stress he has gained from familial conflicts for his symptoms: “During high school, I got into conflicts with my father because I was caught fighting another kid in school. From then on, my family and the school has treated me as if I’m a criminal; and I think I’ve gotten HB due to the mental stress that I’ve received from them.”2 In this narrative, the writer points out his feeling of helplessness that he felt from his family and peers as the main cause of his HB. Also, though it is hard to directly translate to English, his word choice in Korean reveals signs of anger that, together with his sense of helplessness, show his “han.” Regardless of the ethical validity of his treatment by his family and peers, this case illustrates that isolation can cause “han” and in turn, lead to HB. Other narratives reveal a slightly different effect of isolation in their HB experience. In one narrative by a man who says he has been diagnosed HB for over ten months, the writer does not associate isolation as the cause of his HB. Rather, he refers to it as a major side effect after he was diagnosed with HB: “Because HB doesn’t really display any visible symptoms, no one around me understood my hardships and I had a hard time in my social life.”5 From these narratives, it can be seen that HB is also closely related to social isolation. Not only can isolation cause HB, but also HB can cause isolation that in turn, worsens the experience of HB.

Another cultural significance of HB commonly shown in HB narratives is “han” felt from a hostile working environment. A blog post by a traditional Korean medical professional, Im Hyeong Taek, describes his experience of dealing with HB patients. The analysis of this blog post illustrates the relationship between HB and “han” given from the eyes of a clinician:

Just a few years ago, most of the HB patients that used to visit me were female housewives in their fifties and sixties. Nowadays more male HB patients in their thirties and forties come and visit me……The thirties and forties male HB patients usually have worked in the same company for over ten years and feel like they have no one on their side, although they do work with other people. Occasionally, they get the credit for their work stolen by partners or bosses and receive undeserved hatred and discrimination due to their friendship with certain personnel.3

Similar to the previous narratives, the elements of “han” can be seen in various parts. The feeling of “helplessness” is expressed in the form of “feel[ing] like they have no one on their side” and the unfair hatred and plagiarism of work corresponds to the unjust element of “han.” The most important thing to note, however, is the fact that the doctor has experienced an increase of male HB patients in their thirties and forties. Furthermore, the doctor notes that these patients have different causes for their HB than the middle-aged female patients studied in previous research. This differing experience of HB within different groups of people and the increasing number of HB patients illustrate that the social significance of HB is not limited to gender inequality in the patriarchal social elements of Korea. HB represents different types of “injustice” for different groups of people and consequently illustrates the social issues that change with time and demography.

It is important to note that patriarchal social structure is still a factor in the cultural makeup of HB. Many middle-aged women diagnosed with HB still identify patriarchal social structure to be the main cause of their HB. Hence, previous research, which has been mainly focused on middle-aged female patients, was partially justified to associate HB with the patriarchal social structure. However, focusing on sociological and statistical research on HB in the middle-aged female HB patients gives the false impression that HB is only a feminine disease that arises from the gender inequality of Korea. The different online narratives of HB illustrate different social issues, such as national service, isolation, and working environment, showing that this is not the case. As Segal has claimed in another context, the HB narratives “tell a story” about their writers and the Korean social issues that they feel “han”-full of. The emotion of “han” represented in these HB narratives comes from different origins that show different social issues in Korean culture. As suggested by Kleinman in his article “Culture and Depression,” it is important to understand these cultural contexts of depression-like illnesses, such as HB, in order to learn how the experiences of HB differ for different subcultural groups (952). Using this knowledge, the clinicians and patients can cooperate to deal with HB together and establish a better relationship (Kleinman 952).

It is worth noting that the missing, important key to developing our knowledge about illness perhaps isn’t extra surveys or new experiments. Perhaps it isn’t sociological models based on complex statistical analysis. Perhaps it is reading novels or poems or any form of illness narratives that will contribute to expanding our understanding.

Notes

1. “I Am Going Insane Due to Hwa-byung.” Naver KnowledgeiN, Naver, 05 Feb. 2016, http://kin.naver.com/qna/detail.nhn?d1id=7&dirId=70109&docId=244823966&qb=7ZmU67ORIOuCqOyekA&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=6&search_sort=0&spq=0. Accessed 6 Nov. 2016. The essay’s author has translated this and all subsequent quotations from this website from their original Korean.

2. “How Can I Cure HB.” Naver KnowledgeiN, Naver, 21 Jan. 2015, http://kin.naver.com/qna/detail.nhn?d1id=7&dirId=70109&docId=216034307&qb=7ZmU67ORIOuCqOyEsQ&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=7&search_sort=0&spq=0. Accessed 6 Nov. 2016.

3. Im, Hyeong Taek. “Records of Treatment Cases of Young 30s and 40s Working Patients.” Naver Blog, Naver, 11 Feb. 2016, http://blog.naver.com/drlimht/220623650063. Accessed 3 Nov. 2016.

4. “I can’t get rid of HB even after my service.” Naver KnowledgeiN, Naver, n.d., http://kin.naver.com/qna/detail.nhn?d1id=7&dirId=70109&docId=212220446&qb=6rWw64yAIO2ZlOuzkQ&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=3&search_sort=0&spq=0. Accessed 12 Nov. 2016.

5. “I’ve been suffering from HB for years… Help.” Naver KnowledgeiN, Naver, n.d., http://kin.naver.com/qna/detail.nhn?d1id=7&dirId=70305&docId=125537860&qb=6rWw64yAIO2ZlOuzkQ&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=6&search_sort=0&spq=0. Accessed 12 Nov. 2016.

6. “Am I HB?? What is happening to me??” Naver KnowledgeiN, Naver, n.d., http://kin.naver.com/qna/detail.nhn?d1id=7&dirId=70109&docId=117698638&qb=6rWw64yAIO2ZlOuzkQ&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=5&search_sort=0&spq=0. Accessed 12 Nov. 2016.

Annotated Bibliography

Background:

1. Lin, Keh-Ming, M.D. “Hwa-byung: A Korean Culture-bound Syndrome?” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 140, no. 1, 1983, pp. 105–07.

A peer reviewed article on Hwa-byung cases and analysis of symptoms, this article illustrates three instances of Hwa-byung and analyzes and discusses the symptoms of Hwa-byung and seeks to spread awareness on Hwa-byung so that physicians have a better understanding of the illness and Korean culture when treating potential Korean immigrant Hwa-byung patients. The authors call for further research on Hwa-byung is perhaps impeded in part due to the prolonged description of individual cases. Nonetheless, the article explains the phenomena with some helpful details and facts that do go along with the examples that he gives.

Exhibit:

1. Naver Knowledge IN. Naver, n.d., http://kin.naver.com/index.nhn.19 Oct. 2016.

A Korean community driven question-and-answer site founded and sponsored by a Korean major portal website called “Naver.” Similar to many Q&A format sites, this website features questions about numerous topics made by individuals. Due to its many features such as rankings, approved professionals that answer questions, including clinicians and scholars, it was prolific as a Q&A source and functions solidly as a Q&A site. However, there are some issues with this site, such as prevalence of posts that are in actuality advertisements. This source will be useful as a provider of exhibit source of male narratives on HB that I shall analyze, as many posts often feature narratives to describe their situation/problems. Also many posts are made for the sole purpose of writing their story anonymously and are not really questions but rather narratives. Yet, I should be careful to seed out any possible advertisements. There will be about total of six narratives that I will use as exhibit sources from this source.

2. Im, Hyeong Taek. “Records of Treatment Cases of Young 30s and 40s Working Patients.” Naver Blog. Naver, 11 Feb. 2016, http://blog.naver.com/drlimht/220623650063. Accessed 3 Nov. 2016.

A Korean blog post from a Korean blog called ‘Naver blog.’ As it may already be apparent, this blog site is also a service provided by the Korean website Naver, the same company as Naver Knowledge-in. The author claims that he is a Korean traditional doctor and, judging by his former posts and revealed information, seems to be true. However, due to the informal and uncertain nature of these posts, this source cannot be a reliable source for facts, regardless of how seemingly qualified the man appears to be. Regardless of whether the man is actually a doctor or how good of a doctor he is, the blog posts by him are also narratives about HB that is part of the cultural representation of HB.

Argument:

1. Kim, Eunha, Ingrid Hogge, Peter Ji, Young R. Shim, and Catherine Lothspeich. “Hwa-byung Among Middle-Aged Korean Women: Family Relationships, Gender-Role Attitudes, and Self-Esteem.” Health Care for Women International, vol. 35, no. 5, 2013, pp. 495–511.

A scholarly article from a journal on nursing, this article analyzes the causes of Hwa-byung in middle aged Korean women from the Korean culture and calls for further research on the effect of family relationship problems and gender roles on Hwa-byung. It argues that Korean male are responsible for not changing patriarchal values and consequently causing Hwa-byung in females. It also states that the level of female depression is much higher than the males This article is valuable in that it is one of the few peer reviewed scholarly articles that have been published relatively recently on Hwa-byung. Yet, the author’s call for more research on gender-role and family relationship problem is not supported using any specific reference or example, perhaps due to potential word limit or the diversity of these issues. Nonetheless, this article is used as an argument source to which I argue against its possible implication that this is the only cultural implication of HB. It is also used as a background source for some facts about HB (as the primary sources that it quotes are hard to find).

2. Lee, Jieun, Amy Wacholts, and Keum-Hyeong Choi. “A Review of the Korean Cultural Syndrome Hwa-byung: Suggestions for Theory and Intervention.” Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, pp. 49–64.

A scholarly article that provides a new ecological model to studying HB, this article makes few claims about causes of HB in female HB patients based on other scholarly articles. Though this article suggests a new model of research for HB, few sources that support her model are old and makes some statements about HB that are not necessarily true, such as its definition of HB as a disease arising only in females from female inequality (which cannot be true because there are statistics, narratives, articles, records of male patients as well). Nevertheless her model is not particularly relevant to my research and this article can still be used as an argument source for my paper as it makes some claims on generalized causes of HB that I dispute against by doing my research on male HB.

3. Kim, Nam-Sun, and Kyu-Eun Lee. “Gender Differences in Factors Affecting Hwa-byung Symptoms with Middle-age People.” Journal of Korean Academy of Fundamentals of Nursing, 19, no. 1, 2012, pp. 98–108.

A Korean scholarly article which attempts to fill in the missing research on difference between male and female HB patients. This source compares and analyzes statistics based on a survey from male and female HB patients. However, this source doesn’t include any narratives that could accompany their findings. Nonetheless, this source is useful as an argument source as a source of an argument that I will be somewhat be challenging as I focus on the cultural side of HB rather than the sociological aspect that this paper focuses on.

Theory:

1.Kleinman, Arthur. “Culture and Depression.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 351, vol. 10, 2004, pp. 951–53.

A scholarly article from a medical journal that claims a strong relationship between culture and depression. Urges clinicians to understand the patient’s cultural background when diagnosing depression. This source is useful for my paper as depression is closely related to HB, and has many symptoms in common and discusses the importance of studying culture in relation to depression in great detail. Provides an interesting view on culture and many illustrations of how culture is related to treatment of depression but doesn’t focus on specific examples or data. Regardless, this source can be utilized as a theory source as it justifies the significance of the critical lens of “bioculture,” which I use to look at my topic of HB.

2. Hwang, Yong Hoon. (1995) A Study of Hwa-byung in Korean Society: Narcissistic/masochistic Self-Disorder and Christian Conversion (Doctoral dissertation) Retrieved from ProQuest. (Order No. 9530825).

A scholarly article arguing the connection between narcissism, religion (Christianity) and HB. Describes HB thoroughly and even goes into some possibly relevant historical context. This source offers the theoretical model of linking HB with the Korean emotion of “han” that I would like to explore and utilize in more detail. Provides an interesting relationship between two seemingly distinct phenomena: HB and masochism. However, the article is not too effective in delivering its point (over 200 pages) and uses a special definition of masochism that is a bit complicated to understand. Yet, the source offers various explanation of HB that includes history, emotion and culture, which cannot be seen in any other work and its definition of “han” serves as one of the critical lens through which I analyze HB.

3. Segal, Judy Z. “Breast Cancer Narratives as Public Rhetoric: Genre Itself and the Maintenance of Ignorance.” Linguistics and the Human Sciences, vol.3, no. 1, 2008, pp. 4–23.

A scholarly article arguing that the narratives of breast cancer contribute to the ignorance of breast cancer. This article describes a link between narratives and diseases that I will use to justify my choice of narratives as my main exhibit sources. The source effectively illustrates how the narratives contribute to the shaping of our breast cancer knowledge through various examples of narratives and analogies, but isn’t directly related to my topic. However, it is still used as a theory source to justify the lens of narratives that I will be using.

4. Davis, Lennard J., and David B. Morris. “Biocultures Manifesto.” New Literary History, 38, no. 3, 2007, pp. 411–18.

A scholarly article arguing the strong relationship between biology and culture, and the formation of an academic field called “bioculture.” This article describes the link between biology and culture that is a more general form of the explanation of the link between disease and culture. The source uses somewhat informal language and hypothetical analogies that help the material be more understandable. However, on the same note, the examples are hypothetical and general overall, so may not be a great background source or exhibit source. Nonetheless, serves as a theory source that goes along with the Segal’s article. Also serves as the source of the hook analogy for my essay.